The other day, R – a paragon among builder-handymen, who I had thought would be there for ever – told us he was retiring. We will miss him badly but, I have to remind myself, we were beginning to miss him already, because I had recommended him to so many people, he was no longer easy to get hold of.

It would have been selfish to try and keep him to ourselves, but from now on I will be a bit more circumspect if we should ever find another R, as my husband was when, writing a guide to English parish churches, he left out one or two of our own favourites. We told ourselves, they wouldn’t necessarily be other people’s favourites . . . after all, think of the books one has recommended, or had recommended, which have drawn an uncomfortable blank.

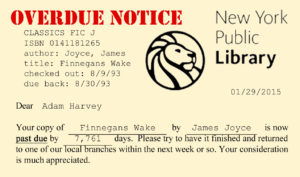

Tastes differ in every sphere of life. We have a lusciously beautiful Italian friend who finds Benedict Cumberbatch irresistible. More baffling still, almost everyone we know likes Breaking Bad, whereas almost no one has any patience with Ruskin (long-winded) or The Wire (impenetrable), which we love. There are even people who read Finnegans Wake for fun.

It doesn’t, of course, matter that we all like different books and different films; nor does it much matter when we over-recommend a workman or keep knowledge of a tranquil, snowdrop-filled country churchyard to ourselves. But it does matter when character recommendations are made in bad faith.

For a long time, when T took over our firm, we thought the colleagues he had left behind must miss him: so lavish was the praise they had bestowed on him. How wrong we were. We learnt – and by then it came as no surprise – that his previous place of work had been happy to see him go. What simpler way to get rid of someone than to heap them with praise?

But, even when truthful and given with the best intent, recommendations can prove treacherous. How could that down-to-earth architect, who had done such a good job for us, run up a bill for twice the original estimate for our neighbours? And what about the solicitor who not only grossly over-charged another friend, but produced a legal document full of spelling mistakes?

Never again! No more recommendations. And yet, when asked to give a character reference, how can one refuse, even though one knows that references are barely worth the paper they are written on and no more to be trusted than those effusive quotes on book jackets. Once you discover that these are often solicited from the author’s friends, you realise they can be as meaningless as the TV ads which guarantee that products will banish acne or deliver eternal youth.