How, I have been wondering, can I make people understand how wonderful this book is? I have just finished Evgenia Ginzburg’s Within the Whirlwind and I want everyone I know to read it. To experience it. It is no help to find it is out of print so I can’t, as my immediate impulse was, buy a few extra copies but, even then, as I know from the pile of unread books on my table, having a book is no guarantee of its being read and someone else’s liking it is no guarantee that you will.

Getting something read was a constant problem during my working life. Neither of my employers (André Deutsch and Tom Rosenthal) could wait to get their hands on the latest Mailer or Updike, but to get them to read something by someone no one had ever heard of . . . I still remember having to reject the then unknown Peter Carey, and if André had read either of Edmund White’s first two novels he might not have been so ready to reject A Boy’s Own Story, which made the author’s name and increased his value a hundredfold. With Tom it was a little easier: the trick was to point him towards any ‘dirty’ bits.

But though I spent thirty years paying attention to every book or manuscript (it was manuscripts in those days) that came into the office, and had the thrill of discovering some wonderful writers among the dross, I could be as obtuse as my two employers when left to myself. It took me several years to get round to reading the two books I now value above all others. Both looked forbidding.

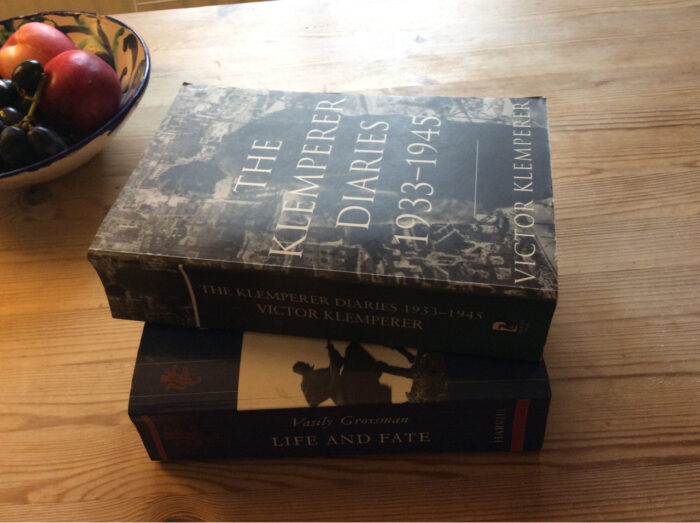

Klemperer’s diaries had been among R’s books for years. The volume was immensely fat and the diary form wasn’t appealing. I don’t know what eventually made me pick it up, but I do remember it was in the early Trump days and how frightening it was to find history repeating itself. I also remember being unable to put it down, as one entry followed another and this love story, for that is what it is (among so much else) slowly unfolded. As for Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, that too waited several years before I picked it up for the second time. The first had been when I saw it lying on a blanket, along with a saucepan and a lot of trinkets, at a boot sale in the North Yorkshire village of Hutton-le-Hole.

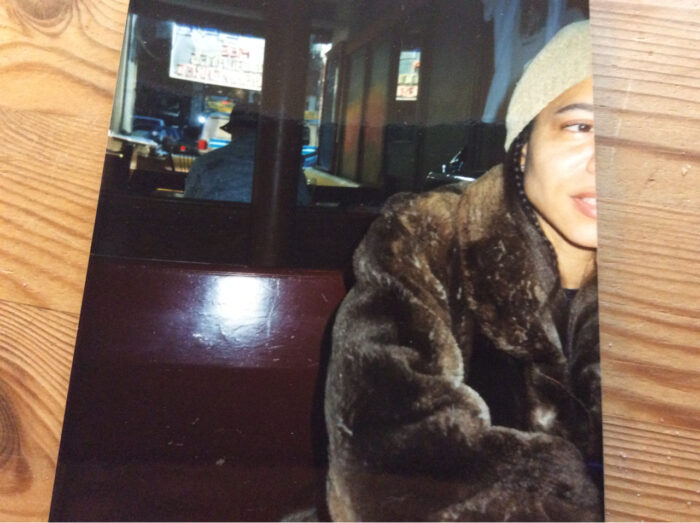

Boot sales. Realms of the great unwanteds. I think the lady asked a pound for it. The same amount that I had paid a few weeks previously for an unblemished copy of the Times Atlas. But not quite as much as the £7 that I was to pay for a beaver coat with a slightly worn lining that now belongs to my daughter-in-law and helps keep out the New York winter cold. A treasure trove of discarded clothes, surplus crab apples, mysterious-looking tools – which our farmer landlord said were bound to be stolen – and pile upon pile of Catherine Cooksons. And among the rubbish, just as among the flood of words that reached me every working day, there might always be something.

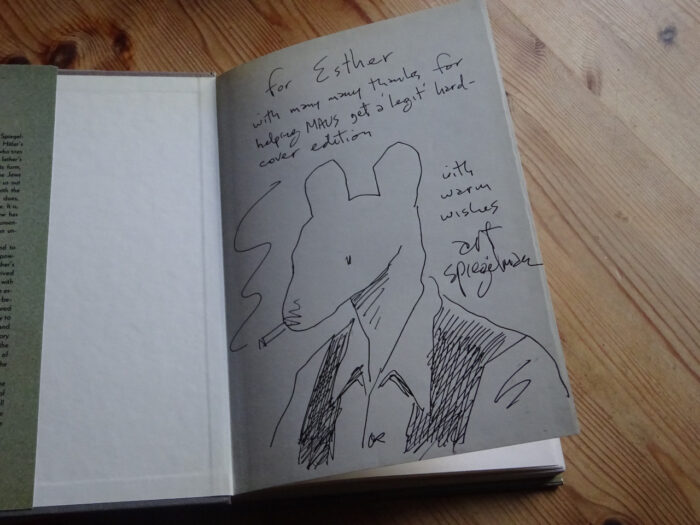

On what proved to be a memorable occasion, the something looked particularly uninviting. The pages of the book-length cartoon sent in by an agent were not even in order and, with comics being one of my several blind spots, I was tempted to return them unread. As it was, the moment I pulled myself together and stepped inside, I was spellbound. What I had in my hand was Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

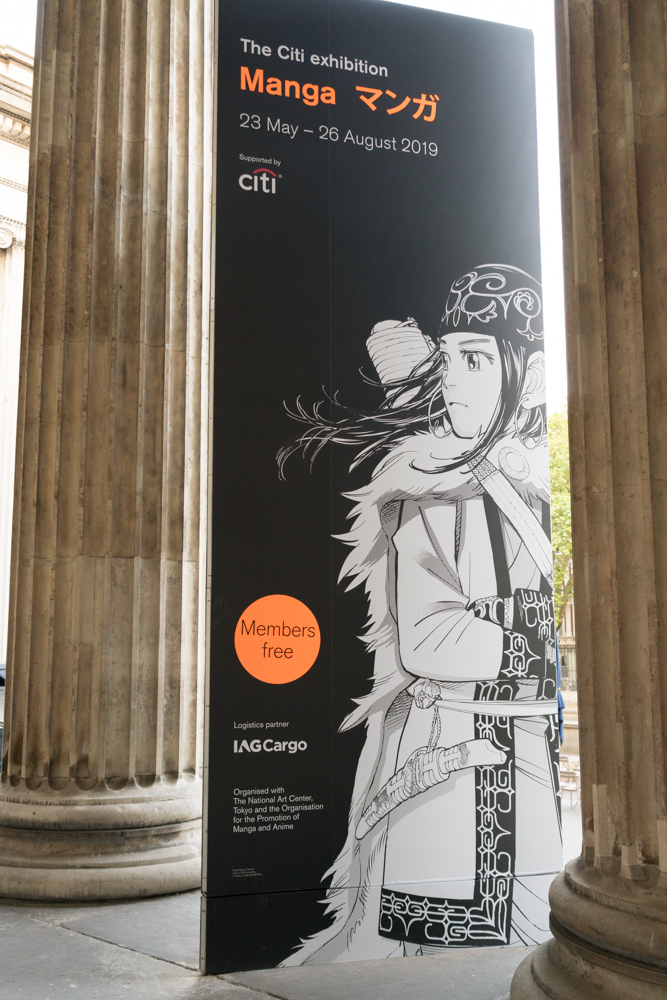

I wish I could say that that experience has made me any more open to graphic novels. It hasn’t. But it was graphic novels which, indirectly, led me to Within the Whirlwind, for I came across it as I was scouring R’s shelves for anything Japanese – novels, films, whatever – for my thirteen-year-old grandson, a veritable scholar of manga. The manga exhibition at the British Museum had been the high point of his last visit to London and the last thing he was to do with his grandfather who, unlike me, was ready to enter an alien world.

My own reluctance suggests that a venture I heard about the other day will fulfil a real need. The aim of the London Literary Salon is to help its members come to grips with those difficult books they have always wanted to read but never had the courage to tackle. The hurdle is unlikely to be the title itself – though Praeterita stopped me in my tracks for years – but size and reputation. If Toby Brothers’ encouragement can get people past the first post, never was being lost in a big, long, ‘difficult’ book a better place to be.