Apologies for the inordinate length of this post, but I am recycling a failed entry for an Oldie competition which specified 1,000 words and provided the title.

After a series of holiday jobs which included working in a filthy Lyons teashop, supply teaching at a primary school in Poplar, where the only quiet moments came when my little charges were lying on their cots masturbating, and being moved from counter to counter in Harrods for being rude to rude customers, the sedate book-lined reception area at Methuen, where I sat waiting to be interviewed for the job of secretary to one of the senior editors, spelt salvation.

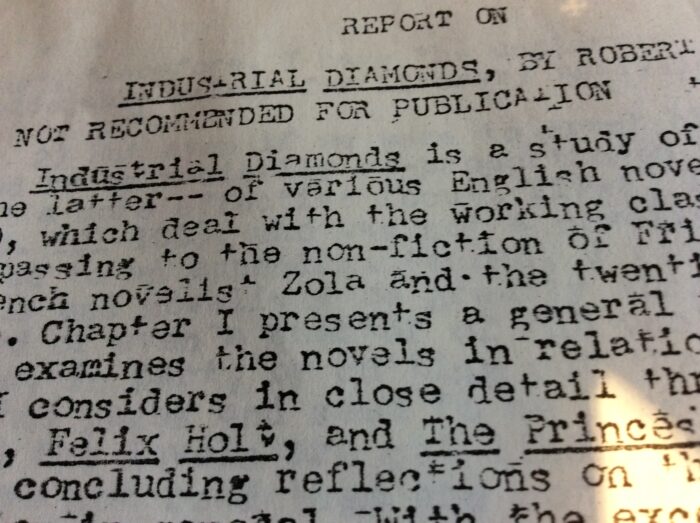

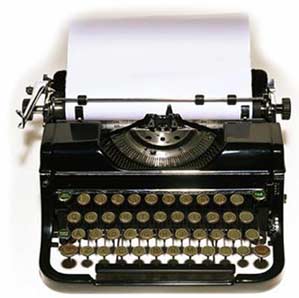

Hot-foot from a high-speed graduate secretarial course where I had almost learned to type, and could read back most of the squiggles in my shorthand notebook, my chance of passing any skills test wasn’t great. But there was no test. The pleasant, slightly grizzled man, to whose office I was directed by the pretty girl at the switchboard, was more interested in what I was interested in than in my speeds, and all I had to do was convince him that I wouldn’t be bored. And a few weeks later, for this was early December, he gave me a copy of Tolstoy’s Resurrection – which I treasure but still haven’t read – instead of the routine box of chocolates.

That my boss had over-estimated my cleverness became apparent all too soon. Not only was I painfully slow getting his dictated letters back to him to sign in a form fit to send, but I had to ask how to spell geriatrics (Gerry Atrix) which I thought was a proper name.

It is hard to imagine how a word that belongs in the Social Sciences could have occurred in any letter of his, for his bailiwicks were the more traditional disciplines of the Classics and Eng Lit, and many of my laboriously produced letters were addressed to the editors of the Arden Shakespeares and, a fair number, to the unrepentant author of a book about Greek vases which was already ten years overdue.

I loved the pace of life which took these glitches in its stride, but it would be a mistake to think that life was dull in Essex Street. Not only was there the excitement of the very first Tin Tin, which had just been translated by the editor who worked in a little room off ours, but I had been mesmerised by the androgynous creature who had joined the other secretary and me and the whiskery old lady who banged out the Rights Contracts at the corner desk in our room.

I loved the pace of life which took these glitches in its stride, but it would be a mistake to think that life was dull in Essex Street. Not only was there the excitement of the very first Tin Tin, which had just been translated by the editor who worked in a little room off ours, but I had been mesmerised by the androgynous creature who had joined the other secretary and me and the whiskery old lady who banged out the Rights Contracts at the corner desk in our room.

The ‘other secretary’ was a proper secretary, from a nice home in the shires, who had attended Mrs Hoster’s Secretarial College in the Cromwell Road: a sweet young thing who was soon to leave us for a job in Buckingham Palace.

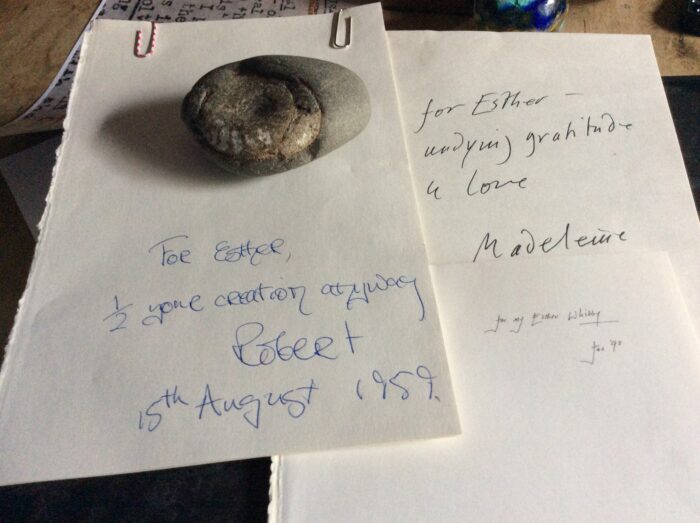

The exotic dark-skinned newcomer was something else entirely. She hadn’t needed to go school to learn to type. She had been typing away for years at a hugely ambitious novel, supporting herself by ’temping’, as so many aspiring artists – and Aussies doing Europe – did in those far-off days when you could walk out of one job in the morning and into another in the afternoon.

The memory of the lunch hours the two of us spent together, she smoking her Gauloises while I ate the sandwiches my mother had made, me drinking in the story of her life, will stay with me for ever. But even her goings-on – all those men she had used and discarded like old flannels – were nothing compared to what came next.

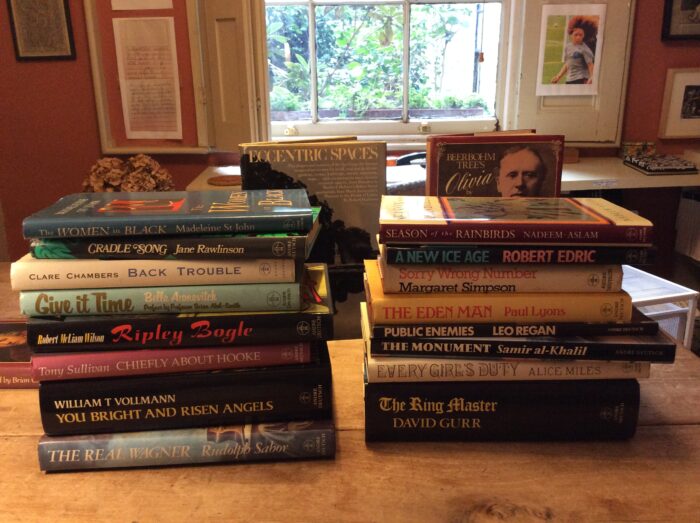

Another denizen of that venerable publishing house was the young continental salesman who, when he was not travelling, would hang about our office and soon revealed that he, too, was an aspiring writer, and gave us his manuscript to read. Not for another twenty years, till I had Edmund White as an author and read States of Desire: Travels in Gay America, was I to encounter anything like it.

To find that this mild-mannered young man led a rampant sex life in hotel rooms all over Europe, taught me a useful lesson. I never again expected a writer to resemble his or her work and was therefore less surprised than my colleagues at André Deutsch when, years later, the author of a rumbustious novel that had made us rock with laughter turned out to be an ill-tempered, middle-aged soak.

But meeting authors was not yet part of my job. I would escort my boss’s visitors to his door, and then see them out again. Maybe I made them tea. I no longer remember, but think there was an ancient tea lady and that it was not until my next job, as Girl Friday to the exuberant Anthony Blond, that I would perform this service for his many visitors, of whom the most frequent were Simon Raven, ever courteous, ever short of cash; and a character called Burgo Partridge, who I remember only as a dark and glowering presence.

Anthony Blond

I was never to have as much fun again as I did at Anthony’s where my duties stretched from sifting manuscripts to interviewing a new cook, and where I was left to run the office on my own – and start up the Bentley each morning – during his frequent absences.

At Methuen, life had been altogether more orderly and secretaries did only what secretaries did, which was take dictation, type letters with carbon copies, file the copies and, at the end of the day, put the typed letters in their typed envelopes into a post tray for someone more junior still to collect.

But, every now and then, I would be given a set of galleys to correct. The responsibility was intoxicating! And it was these rare occasions, when I was able to leave the shared office and lay my precious burden on the massive mahogany table in the book-lined boardroom, which made me certain that though I was only on the first step of the ladder, it was the right ladder for me.

I loved the pace of life which took these glitches in its stride, but it would be a mistake to think that life was dull in Essex Street. Not only was there the excitement of the very first Tin Tin, which had just been translated by the editor who worked in a little room off ours, but I had been mesmerised by the androgynous creature who had joined the other secretary and me and the whiskery old lady who banged out the Rights Contracts at the corner desk in our room.

I loved the pace of life which took these glitches in its stride, but it would be a mistake to think that life was dull in Essex Street. Not only was there the excitement of the very first Tin Tin, which had just been translated by the editor who worked in a little room off ours, but I had been mesmerised by the androgynous creature who had joined the other secretary and me and the whiskery old lady who banged out the Rights Contracts at the corner desk in our room.