Diana Athill, who has appeared several times in these blog posts, died on 23rd January 2019.

This is the story of our friendship. Told to myself, to try and make sense of it. I feel able to post it thanks to Diana’s nephew, Phil Athill, without whose approval I would not be letting it travel outside the room in which it was written. Disconcerted by the media gush that followed her death, and hoping for a serious and cool reconsideration of her life, he encouraged me to send it to a national newspaper, but I hesitate to try to publish more widely something that was written to purge my own feelings and which could cause anger and disappointment to the many admirers who knew Diana only from her books and the idealised version presented by the media.

In this form, it is in keeping with the principle of my blog, which is to talk about what concerns me at the moment of writing, or has interested me or concerned me in the past.

The funeral was only a few days ago. A joyful affair. For how can one mourn a life that lasted for over a hundred years and was fully lived until the very end? The solemn tolling of the church bell as the coffin was borne away was a fitting prelude to life-after-Diana for all of us gathered there, now drinking champagne and sharing our memories in her now for-ever absence.

An absence that I was to feel acutely the next day as I read the last page of a novel I had picked off the shelf in my son’s Brooklyn home a few days before. I had never heard of the Danish author of this remarkable book and I am sure Diana hadn’t either, for she would have told me about both it and him . . .

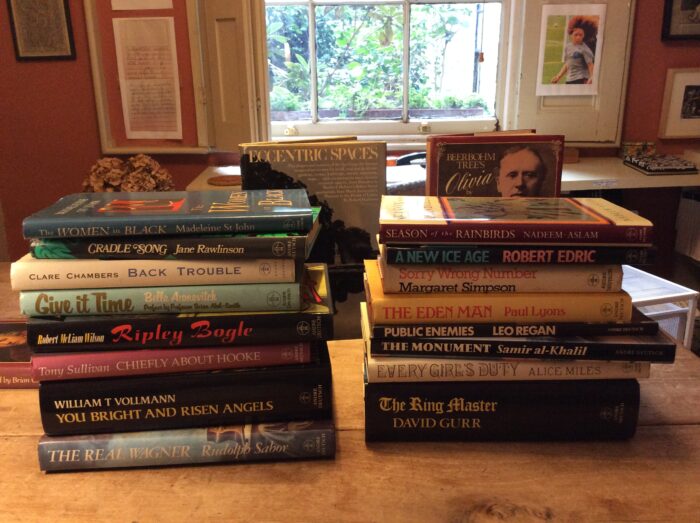

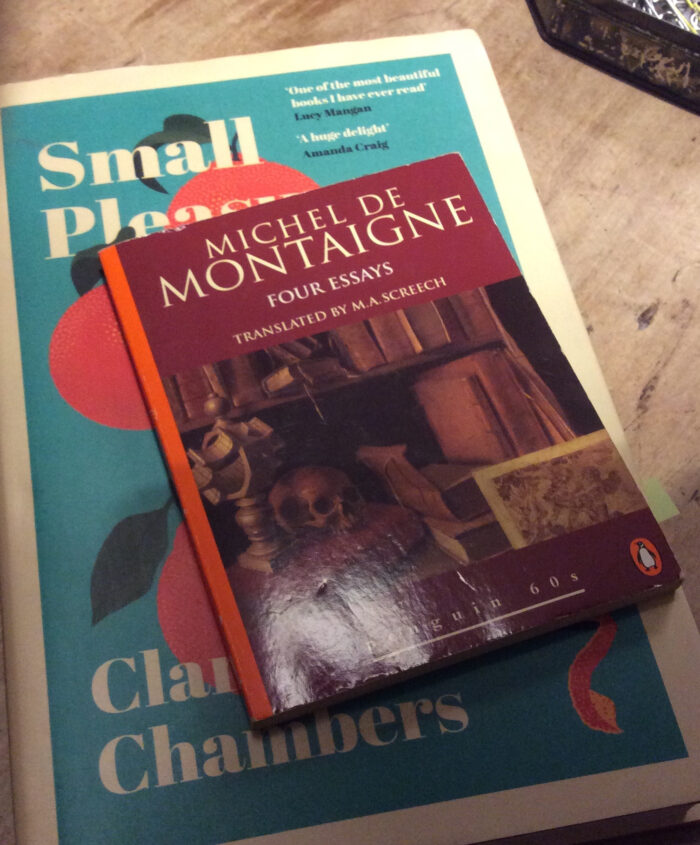

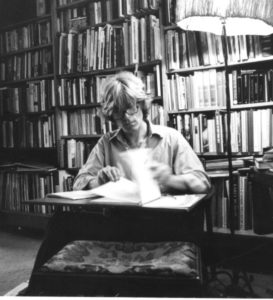

During all the years she spent in that Highgate home, familiar now to her thousands of readers, I would take her books I had been reading and would look forward, as I had done during the thirty years or so that we worked together, to knowing what she thought of them. Her taste (within its confines) was unerring and her love of books unparalleled.

It was this that I valued most in her, and it is this that I will miss, that I miss already. Who else would have made me think again about James Salter? Swept up, like everyone else, by the media attention he attracted on his death (I had not heard of him before) I fell for All That Is, and it took Diana to make me think again. She was not moved by this artifice and, on re-reading him, I became uncomfortably aware of how shallow the book was beneath its glittering surface.

And now that I have come across another novel whose subject is the intricacy of married life, she is not there to test it out. But I like to think she would have thought Jens Christian Grondahl’s Silence in October as extraordinary as I do, a serious challenge to one of her own authors who had made marriage and family life his territory.

John Updike is one of the authors on whom Diana’s reputation as a great editor – ‘the best editor in London’ – rests. An irony of which she herself was aware (she never claimed greatness), for John Updike, like Norman Mailer, that other giant in her stable, was actually edited not in London but in New York.

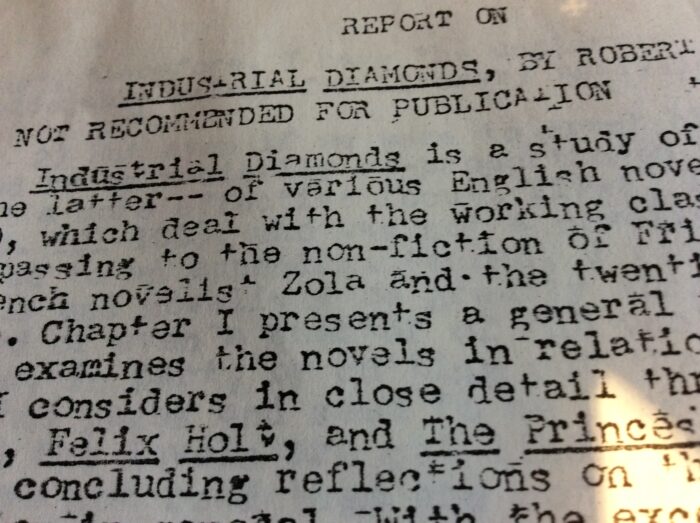

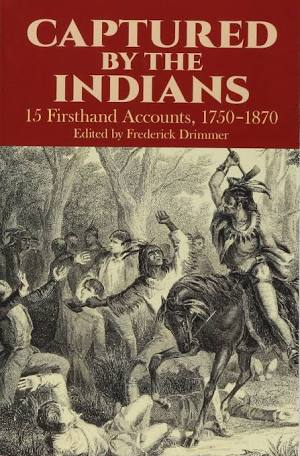

As for Jean Rhys and V.S. Naipaul, whose miraculous re-discovery and discovery are always attributed to Diana, they had already been snuffled out by that remarkable truffle-hound, Frances Wyndham. Indeed, Jean Rhys was of so little interest to anyone at Deutsch – except as an irritant to André, who had paid her an option of £25 and received nothing in return – that I, then the most junior editor, was sent down to Cheriton Fitzpaine to try and get the book out of her. The novel, which I helped assemble, was The Wide Sargasso Sea.

Without Diana, the Jean Rhys story from then onwards – or, rather, from the time, two years later, that the manuscript was delivered – would have been very different. An editor’s job is twofold: attention to the text and attention to the writer, and at the latter – the nurturing – Diana excelled. And it was this that Jean Rhys needed, and without which she would not have survived.

Despite the poverty and isolation of her life at that time, the manuscript that Jean handed in could have gone straight to the printer. Naipaul’s submissions were also word-perfect, leaving little for an editor to do. I know this from experience, as I had the unnerving job of being the first to read A Bend in the River, which came in when Diana and Vidia were barely on speaking terms (entirely his fault). I did my best to find something wrong: to be able to make a few suggestions which would show that I had read the book with attention. But it wasn’t easy. And, though I passed the test (admiration, whether genuine or feigned, goes a long way) I was very relieved when Vidia thought better of breaking with Diana and I was shot of him once and for all.

Relieved because, like Jean, Naipaul demanded (in his case, demanded rather than required) constant attention. His ego knew no bounds and I wonder if the greatest of all editors – Maxwell Perkins – would have considered him worth putting up with.

Editor of Genius is the sub-title of Scott Berg’s life of Perkins, which I had picked up in a charity shop and both Diana and I read at a gulp. Here, we agreed, was a great editor: a man of heightened sensibility who never wrote himself but who harnessed the talent of writers as diverse as Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe, paying even more attention to the fabric of their books than to the fabric of their lives, whilst totally immersed in both.

An obsessive attention to the text, which is the prerequisite of the great transformative editors (like Charles Monteith or Ezra Pound), did not come naturally to Diana: too time-consuming for someone whose life was lived largely outside the office and who was to start writing herself. But this did not blunt her greatest gift to her authors, which was her initial understanding of and pleasure in their creations. After that, as far as the text went, it was broad brush strokes only. The rest could be left to the copy-editor.

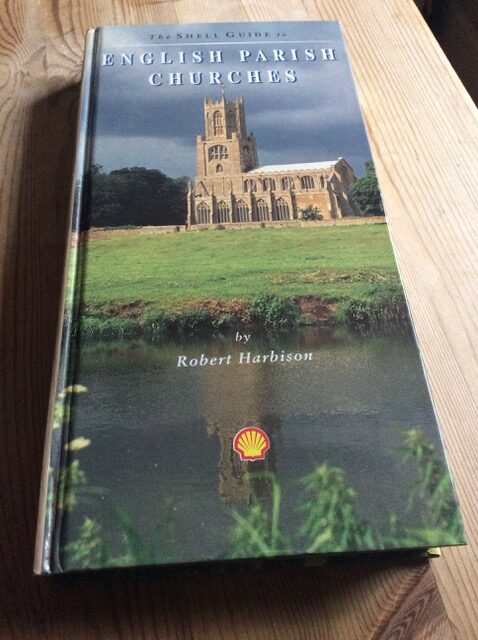

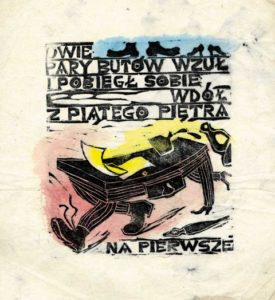

For the hopelessly dutiful such insouciance is enviable. What does it matter, after all, if one book slips through without one of those infernal Advance Information Sheets which we were required to dream up to try and enthuse our salesmen? The book in question was one of my husband’s: Deliberate Regression: the disastrous history of Romantic Individualism in thought and art, from Jean Jacques Rousseau to twentieth-century fascism. I couldn’t understand every word of it myself and now have a copy, annotated by the author, which explains the bits that foxed me, but I would have come up with something. I wouldn’t just have said, as she did to me, that you would need a wet towel to wrap round your head to read it, and left it at that!

But that was Diana. Enviable in her lack of guilt. An English thing. A class thing. Certainly not a Jewish thing. It is hard for me to imagine not being conscience-driven. Life without Jiminy Cricket, what licence that would give! And it did.

The whole world knows about Diana’s love life, and many of those who cared for her were glad when she stopped being a spokesperson for serial infidelity and for sex in one’s dotage, and instead became a champion of fearless dying. But during those years, while women in her audience – for many of whom sex had not ceased to matter but was contained within marriage – listened avidly to tales of deception which could have involved their own husbands, or their daughters’ husbands, the real Diana was lost sight of.

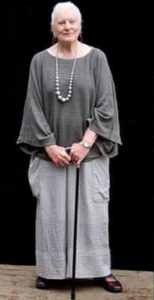

There was so much more to her than that. For it takes strength to defy convention, and this strength was manifest in behaviour far removed from the sexual shenanigans served up cold in one obituary after another. It was not only her calm acceptance of approaching death but her refusal to let the strictures of old age – the difficulty of getting in and out of a car, the loss of taste and hearing – get the better of her, which singled her out from the moaners and groaners, among whom I count myself.

She was not a complainer.

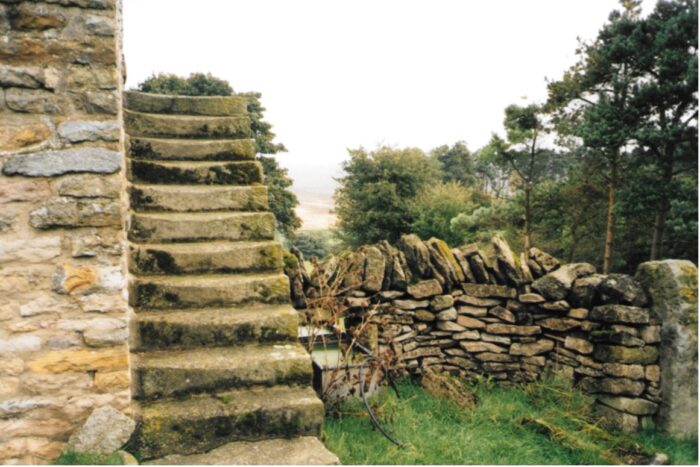

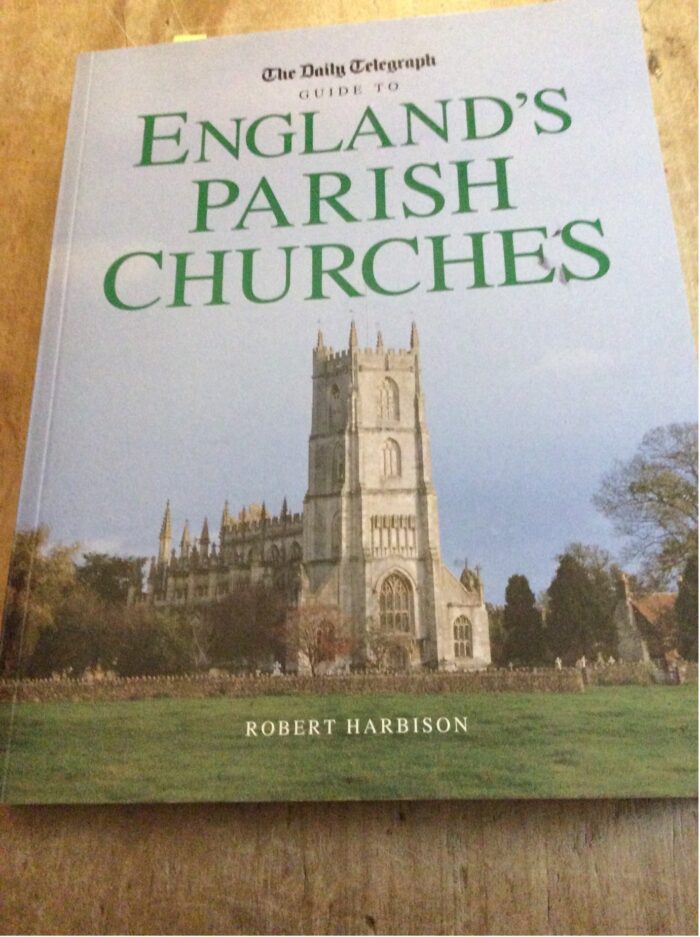

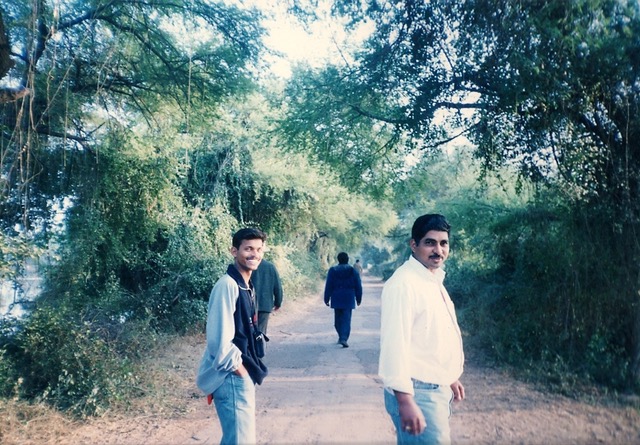

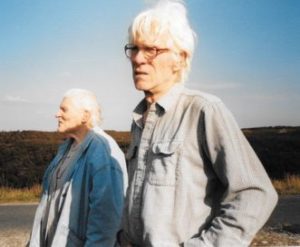

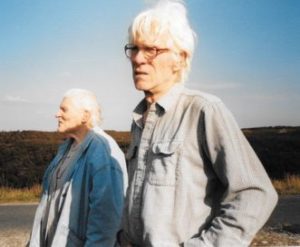

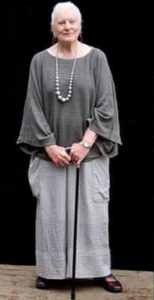

Diana in Yorkshire, with my husband, Robert Harbison

I remember her telling me how she had fallen during the night, while staying with friends,but had waited to get help till her hosts appeared for breakfast, after which she was taken straight to the nearest hospital. And when she came to stay with us in Yorkshire, already in her nineties, she was not content to look at the glorious moorland landscape from the car: we would stop and she would get out, however muddy or uneven the terrain. This, after all, was the land of her Athill forebears . . .

Most of them, anyway. For, as I learnt only a few days after Diana’s death – so we never had a chance to talk about it – the sugar island of Antigua had been the improbable birthplace of one of them. I happened to be in Antigua, on my way to New York, when Phil Athill, Diana’s beloved nephew, and perhaps closer to her than anyone else in the world, e-mailed me about the revised funeral arrangements. On learning where I was, this was his immediate response:

‘Antigua! Athill homeland. Diana’ s great-grandfather, George, was born there in 1807 to the Chief Justice James Athill and one of his octaroon slaves. He was officially a Man of Colour . . .’ And it ended: ‘Please take a walk down Athill Street for us!’

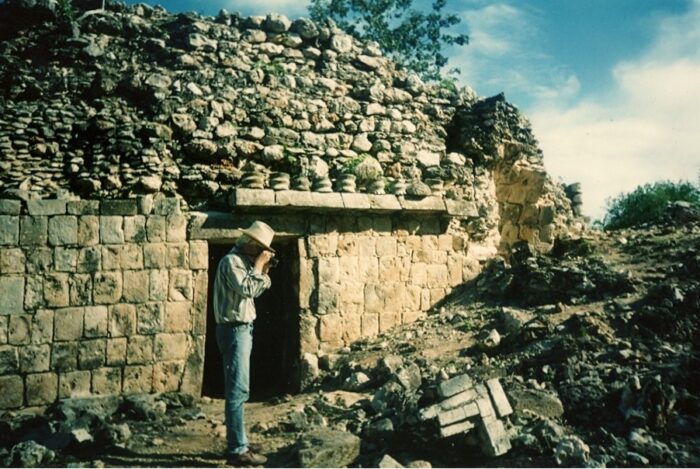

Me in Athill Street, Antigua

I did, of course. And at the same time marvelled at how history repeats itself. Diana, that lovely, leggy, horsey English girl, who was soon to have her heart broken, as all the world knows from Instead of a Letter (which remains, for me, the best and most moving of all her books) had gone on to share her life with a succession of men of non-white descent.

A chip off the old block, my father would have said. It was not until I became friends, quite recently, with a West Indian of near Diana’s age, and learnt he found her much publicised predilection for black men offensive, that I thought of how it might seem to non-white males.

It was this same friend who told me that Naipaul’s early novels did not endear him to the people amongst whom he grew up. But that wouldn’t have bothered Naipaul, and what I most admire in him was his courage in allowing his biographer a completely free-hand, which is what – some years later – Diana allowed me . . .

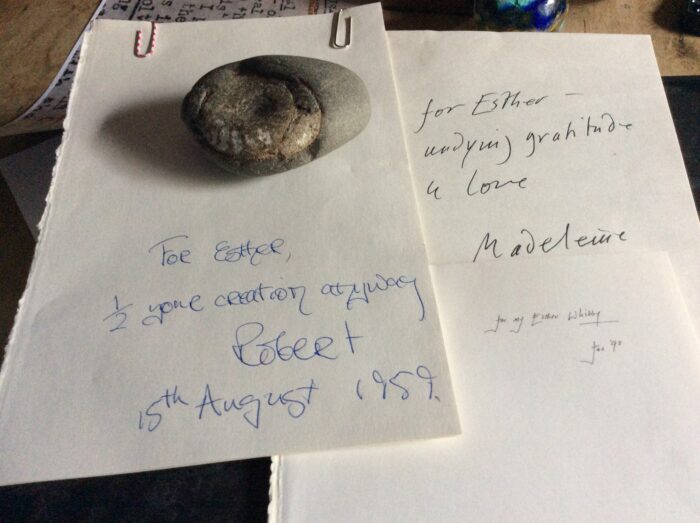

Some twenty years ago now, the manuscript of a book I had written about my family and my years at Deutsch was spread out on the table, when Diana unexpectedly called in. Written without thought of publication, and thus with no holds barred, the frequent references to Diana showed her both at her best but also at her worst. And now here she was, wanting to read it and dismissing my mutterings about it not always being very nice about her. ‘There’s always something we don’t like about our friends,’ she said, quite equably, and carried it off.

Two days later we met in a teashop in Regent’s Park Road where she gave me back the manuscript and, with it, an odd-shaped parcel. Inside, was the Staffordshire figure which I had always regretted not being quick enough to buy myself: an incident described in the book. Neither that nor my account of the Molly Keane affair – of which the less said the better, for it caused a rupture that never quite healed – had stopped her in her tracks: she did not ask me to change a word.

In fact, she even offered to write a foreword, though I thought better of asking her for this when, many years later, the book, Loose Connections: from Narva Maantee to Great Russell Street, was published. The eleven-year delay had ended with our one-time employer’s death. You cannot libel the dead and, as he and I were the same age, it had become a race against time. Who would go first? Now, the phone calls from friends, anxious for me to be able to publish, reporting on his health – one person had seen him in the swimming baths, another at the opera – became, like him, a thing of the past.

Diana’s magnanimity in not asking me to change anything was remarkable. But so was she. Never more so than in her attitude to the Birthday Book that her well-meaning young agent devised to celebrate her illustrious client’s hundredth birthday. This comprised thirty or so hastily written tributes from authors, work colleagues, family and friends which her publisher turned into a handsomely bound volume, to be presented to Diana at the party given to celebrate her birthday.

At the party itself, over which Diana, dressed like an empress, presided in a wheelchair, I distinguished myself by having pressed the wrong button on my new digital camera and coming home with pictures only of people’s feet. Which was a pity, as I would love to have a good photograph of Diana surrounded, as she was, by those who loved and admired her, plus a happy scattering of little people – great-great-nephews and nieces – who enlivened life below knee level. Only dogs, which Diana and her closest friend, her cousin Barbara, had loved all their lives, were missing.

Unable to do more than catch a glimpse of the book to which I had contributed as it was presented to her (and which, as I could see from a distance, she was having great trouble removing from its wrappings), I asked, the next time I went to see her, if I could have a look at it.

The answer was No. She didn’t know where she had put it and she was in no hurry to find it. She had clearly found the whole thing mildly embarrassing. The obverse of Diana’s ‘beady eye’ – that splinter of ice, which could be so unnerving – was immunity to emotional gumbo.

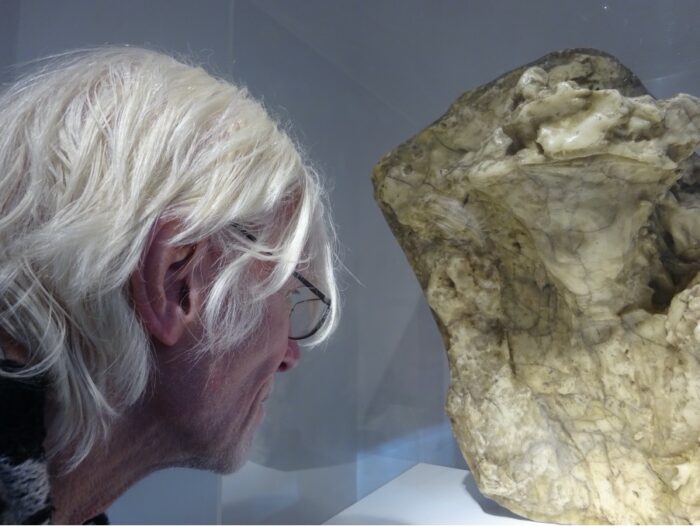

I am left wondering whether she even read all the entries, but I hope and believe she didn’t need to be told how much she had meant to so many people. And I shudder slightly at the thought of what she would make of this thing I am writing now: not because it doesn’t present her as perfect, but because she was impatient with sentiment. Impatient with sentiment and not easily fooled. Despite enjoying her celebrity, she never really took it seriously and remained what she had always been – an exceptional responder to beauty, in all its forms: not just the written word, but the magnolia tree outside her window, the window boxes full of lovingly chosen flowers (our expeditions to nursery gardens are among my fondest memories), the exotic clothes she could, at long last, afford to buy.

And she never lost the qualities which make her such a sorely missed friend: I love the beautifully handwritten, gossipy letters I received when I hadn’t been able to get to see her for a while. As for the visits themselves, no one was better company and though I will remember with lasting pleasure the times we spent together in the room which became her home, my happiest memories will always be of the car rides back from the office, when we would cross Russell Square to collect her car from the vast underground car park, and then sally out into Tottenham Court Road where – talking all the time, as though we hadn’t seen each other for years – we belted along, through the rush-hour traffic, as if ours was the only vehicle on the road.

Only death could have stopped us talking, and now it has.