Although my last blog post had been written for my own amusement, I did, in fact, send it to The Oldie and it came winging back the very same day as being ‘not quite right for us’.

Having rejected some thousand manuscripts myself, I had never been quite as quick as that, allowing even outlines to spend a few days on the hallowed premises of a publisher’s office, affording these would-be authors a few days of hope.

Perhaps it would have been better to stifle hope, but who wants to be responsible for nipping talent in the bud? And one could be wrong. I still remember the occasions on which I came across reviews of books I remembered having turned down.

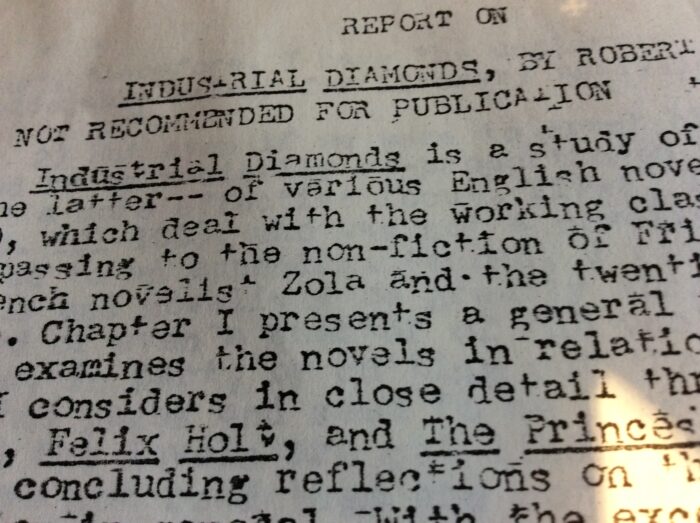

Of course it is now more than fifty years since three old codgers in the English faculty at Cornell decided that my husband’s PhD thesis* was not worth publishing, thus shattering his belief in himself, which was only restored when a year or two later his landlady (me) came across her lodger’s dog-eared typescript (what was I doing poking about in his room?) and loved everything about it, that is to say the qualities – above all the wit – which, along with rarefied scholarship, were to be his trademarks.

Narrow-mindedness is, of course, a requisite of regular academics and it was inevitable that R’s brother, a well-respected art historian, should throw up his hands in horror at the lack of specificity in his older brother’s books.

That, some years later, R was invited to spend a year at Cornell as a kind of honoured guest is the equivalent of the way in which, in the publishing world, the obscure origins of a prize-winning author who once fought to get anyone’s attention are long forgotten.

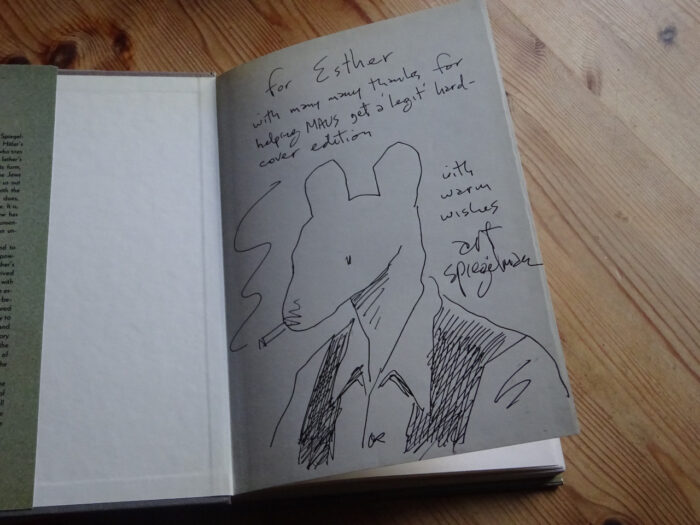

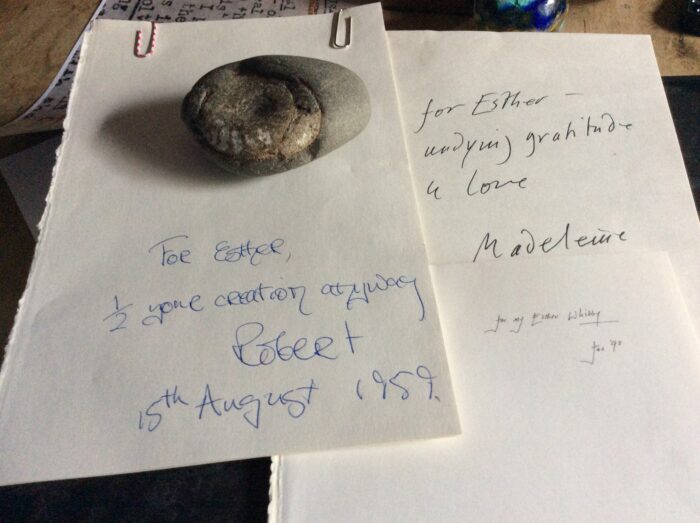

Forgotten by the publishing world – including the agents who, as they trawled our catalogue, now ‘discovered’ these writers they had, of course, seen before – but seldom by the writers themselves. I treasure the continuing friendship of many of those I helped to get started and am amused by the inscriptions of the ones who preferred to forget:

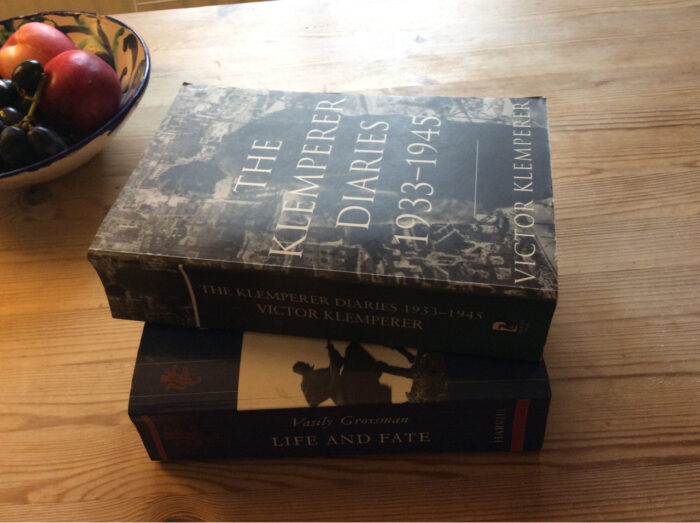

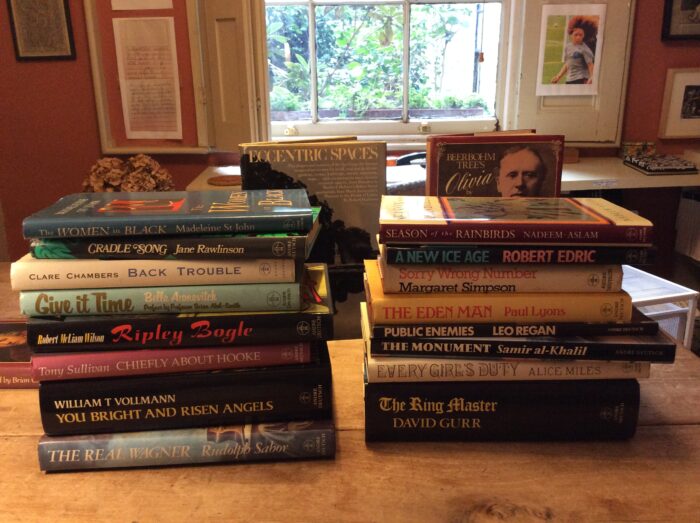

But I don’t, of course, wish I hadn’t taken them off those piles of un-agented manuscripts known as the Slush Pile, which no longer exists but was the life blood of the pre-digital publishing world. And I am left with no regrets about those I had to turn down because no one liked them as much as I did, or André took against them: Eva Figes, Peter Carey and Carl Lombard among them. They soon found a home, as did my husband’s book which is seen in the photograph in its American edition (our own budget didn’t run to using an Atget photograph).

*Industrial Diamonds: The Working Class in English Fiction 1840-1890