Two years ago, at the age of eighty, I published my first book, thus inverting the work of a lifetime in which — as an editor — I had nursed other people’s books into existence. It was, and remains, quite an experience.

The actual writing of my memoir is hard to describe, but what it most felt like was pulling a thread: no effort was needed, just a few uninterrupted hours — surprisingly hard to come by even though I was by now long retired.

My husband (also a writer, but a serious writer, whose many subjects do not include himself) manages to get time for himself every day, but it seems that a woman’s work is never done, even if it is only answering the door bell, scrabbling through the freezer for tonight’s supper or getting a late birthday card into the post.

But the days on which I was able to pin ‘GONE FISHING’ on the door of my room mounted up and, at the end of three years, this record of my life — three decades of which were spent working alongside the legendary Diana Athill at André Deutsch Limited — was complete.

It was only then, reading what I myself had written, that I realized how indignant I felt on behalf of women, both at home and in the work place: a dyed-in-the-wool feminist, without even knowing it!

Here follows just one example from my book which, in recalling all those years as a literary midwife, contains many others.

‘A parental “Where’s the novel then?” or words to that effect were, apparently, what finally spurred Howard Jacobson to get down to his first book, but the havoc that writers create in the lives of their nearest and dearest spreads in all directions: not just the worried parents, but the partner who may never know the luxury of a regular income and the children whose childhood is one long admonition to keep quiet: the thud of the football against the back door, the beat of rock music, intolerable to the writing Daddy who expects to have a decent stretch of quiet every day. The writing Mummy, of course, doesn’t expect to have stretches of time, let alone quiet time, when there are children at home and finds different ways around this.

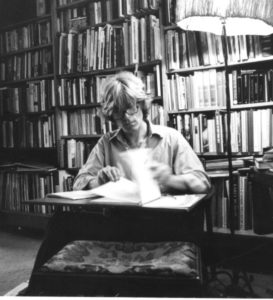

One Deutsch author who began writing when her four children were not yet at school, would snatch time before anyone else in the house was up. (It was her youngest son who told everyone that his mother had written six books after helping her to open the parcel of six complimentary copies . . .) Another, her third child on the way, had, in two years of Monday mornings, completed her third novel and handed it in just days before the baby’s birth. Then there was the twice-divorced father who wrote four entire books (typed on the back of Council minutes) on the train to and from work, returning home to cook the supper and put his four children to bed. For this is to do with mothering, not gender. But most mothering is done by mothers and many, like Shena Mackay, put their careers on hold while their children grow up or, like one of my oldest friends, don’t really get started until their children leave home, getting their first royalty statement at much the same time as their Freedom Pass . . .’

I must, in all fairness, add that not all male writers have an easy time of it. There are men with nine-to-five jobs who find themselves in much the same boat. But one can’t help noticing that it is still almost always the women who have to be the most accomplished jugglers of domestic priorities.