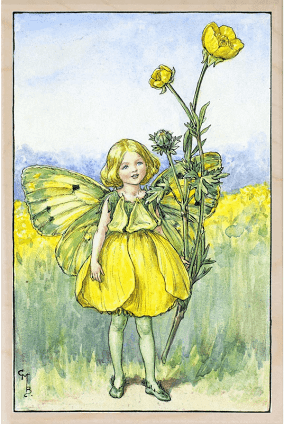

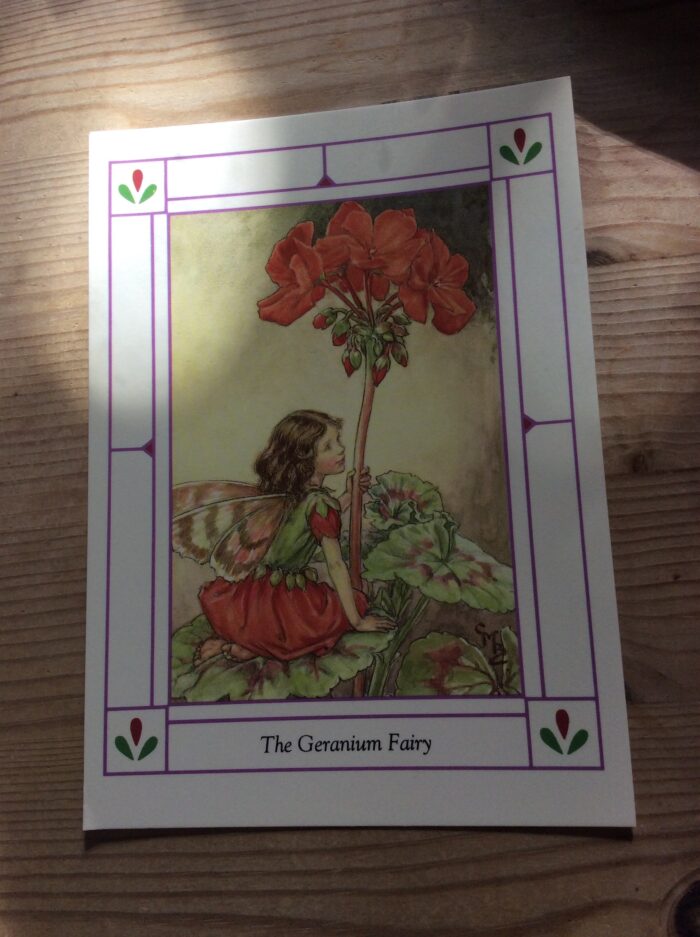

From Cicely Mary Barker and the Flower Fairies to Robert Mapplethorpe is a far cry, and the sudden appearance of the latter in a review of an exhibition of his flower photographs when I had been thinking of blogging about the former, has thrown me.

I had come across this old Flower Fairy postcard and been thinking how much the gifts of flowers during the months that R was at home, waiting peacefully to die, had come to mean to us both. And how flowers had now become a habit.

Unused to spending money on anything except necessities (in a first world sense) I now treat myself to a bunch of something every time I pass our local Lidl.

They have become as necessary to my life as they clearly were to Cicely Mary Barker, a pious Anglican, living with her sister in Croydon where they, the daughters of a seed merchant, had been born.

It is easy enough to see where Mapplethorpe got his inspiration (for copyright reasons I dare not reproduce any of his beautiful, suggestive photographs here but they can easily be found online), but I could not have guessed that the models for Miss Barker’s fairies were the children who attended the kindergarten that her sister had established in their home. This much-loved artist — belonging by upbringing and temperament more to the homely world of the ‘flower ladies’ we met in the several hundred churches I visited with R during one of the happiest times of his life* — evokes a kind of Englishness that no foreigner could ever aspire to. And how much more desirable than the razor-sharp beauty of Robert Mapplethorpe’s black and white studies which mirror his private obsessions.

Here I have to remind myself that R loved not only the common or garden flowers of garden, park and hedgerow which translated so happily into little children with butterfly wings but also orchids, the feral denizens of the flower world.

Entranced by their complexity, he began to collect them and every time we needed to go to Ikea (they were the lure to get him there) meant one more for him to cherish. As for our expedition to the Orchid Festival at Kew, what a different experience from our harmonious church visits that turned out to be. In the steaming heat of the tropical glass house we lost each other.

Glued to a particular bloom, he hadn’t noticed that I had moved on and I hadn’t noticed he wasn’t still following. For more almost an hour I sat at the exit until one of the kind guards who had joined in the fun (for them) of R’s disappearance managed to find and deliver him.

Memories, memories. What else does old age comprise? I remember that flowers were a part of my mother’s life, and will never forget the sight and scent of the freesias, bought off a market stall in the Portobello Road, with which I covered her coffin.

* See R. Harbison, Eccentric Spaces, Foreword.

** Almost every one of the thousand or more churches that he visited evoked a rapturous response. He so loved ‘dark plaster, faded colour, crumbling stone — perishable materials perishing . . . . ‘ (from the Introduction to English Parish Churches). For R, to ‘assimilate more and more to the realm of delight’ was what life was about.