It was coming across Rory Stewart’s choice description of Boris Johnson as ‘a terrible prime minister and a worse human being’ which prompted me to listen again the other day to his, Rory’s, Desert Island Discs, and this reminded me of something I had never understood, which is why we were always hearing so much about Rory Stewart’s father but never a word about his mother.

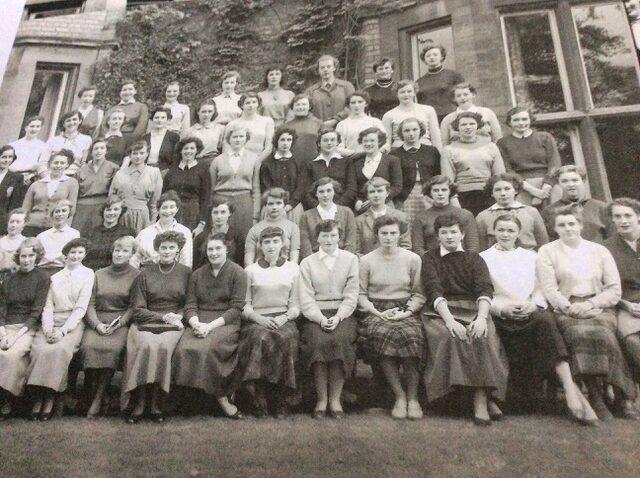

Why am I interested? Well, Sally and I had been in the same year at Oxford in what was then a women’s college and met up, fifteen years or so ago, at one of those overnight college get-togethers, particularly memorable because the electricity failed and my expectation of hot cocoa and gossip went for a burton.

But we had been seated next to each other at the evening meal and it was then I learnt that we had sons of much the same age and now that I know how very remarkable Rory already was, she did not make a production of this. But that was Sally. She had always been exceptionally well-mannered and discreet.

Most of us in that mid-‘50s intake had very quickly paired up, even ganged up, and spent at least as much time talking about ourselves as we did about Chaucer or Milton or whatever; but Sally, though courteous to all, wasn’t a joiner and, thinking back, the only thing we knew about her home life was that she lived in Wimbledon. To discover – in a long New Yorker piece which did mention Sally – that her father was Jewish, was a surprise.

And, hadn’t there also been an earlier husband? I can’t be sure for – with the exception of a couple who had been joined at the hip since day one – none of us actually got married before we went our separate ways. But the pressure to be married, when we were young, led to a lot of false starts. If you didn’t find a husband then, when would you? So it wouldn’t be surprising if, like me, she was on her second husband.

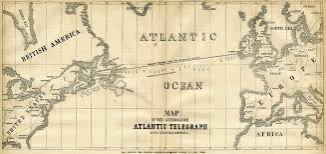

Whether or not, I had a hazy memory of a very tall, very English man – an engineer, a builder of bridges, and talk of foreign lands . . . And any time I thought of Sally, I imagined her leading a Somerset Maugham kind of life in some faraway place. Not a bad guess, as the one fact that googling ‘Rory Stewart’s mother’ reveals, apart from her full name, is that her son was born in Hong Kong.

If my attempt to get Rory’s books out of the local library hadn’t failed (see Now What?) no doubt all would have become clear. As it is, I will always regret that we haven’t seen him in Downing Street over these past few years. And it remains hard to understand why there has been so much in the media about his father and nothing about his mother. Can it really be that in this day and age mothers*, including women like Sally who have careers of their own, are still not considered worth mentioning?

*Our year excelled in mothers. Hugh Grant’s mother is also in that photo (3 rows down and 5 across) and, like Sally and me, she spent her first year living in digs way up the Iffley Road.