It is not hard to remember someone you could never forget.

I am riffling through some of the many, often enigmatic, messages I got from Kemal during the four years that I was sending him second-hand paperbacks for the shelves of his little bookshop in the back streets of Antalya.

This, one of the earliest, is typical:

You have time do box of fiction?

Good evening

I must pay you

Kemal

Luckily, I did have time and those four years, when life was one long treasure-hunt, were among the most carefree ever.

The timing could not have been better. Retired by then from a life working on other people’s as yet unpublished books, I had just given up on the last of several attempts to be useful, and was ready for something new. And so it was that I stopped the numbingly useless attempts to improve literacy in prisons (the bureaucracy, not the prisoners, proved the sticking point) and plunged happily into finding reading for the English-speaking walkers of the Lycian Way in the seaside town of Antalya.

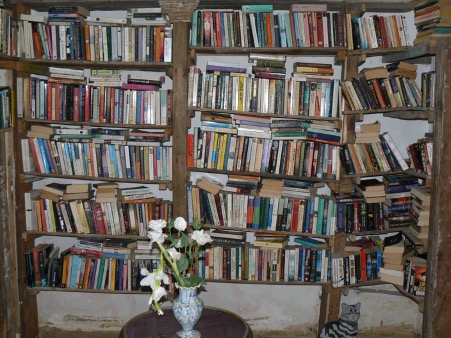

It is said that it was the paperbacks, abandoned by tourists – and found by Kemal while working on the buses – that had propelled him, a young man with little formal education but a passion for books, to start his own bookshop.

Of course, even if this is true, there must have been other steps along the way, and those of us who came to know Kemal have spent many hours trying to reconstruct his past life. It is only very recently that I heard the bus conductor story: a little more likely than the fantasies prompted by signs of a bullet wound on his shoulder.

I never saw his shoulder. We were not in Antalya long enough to join him for his daily swim.

. . . only the dead know Brooklyn by Thomas WOLFE . . .

Take care

I swim every morning

Kemal

and, having told him, almost as soon as we met, that I had a husband, I like to think it was only this that kept him from inviting me to spend a lot more time with him. For Kemal loved women almost as much as he loved books.

One of the many women lucky enough to cross his path was already a friend of mine. Another became a friend. Both treasure his memory and share with me their grief at the news of his death. Which occurred exactly one week before, unknowing, I included one of my own Kemal memories in my September blog.

It was he who hauled that hideous bowl (which I now know was a choice example of Palissy ware) to Sotheby’s, and it was the young woman who had collected it from me who, all these years later, unearthed my address and let me know he was, by his own hand, dead.

. . . next summer I will built my own spulcreve in my willage . . .

wrote Kemal almost exactly nine years ago.

What is all this about a sepulchre? Surely it is a bit early to be planning

your tomb . . .

I wrote back. I had no premonition of what was to come. Nor did he. He had simply found a sculpture (cat sculpture seal by French sculpcure) that he wanted for his tomb, and I can only suppose that now he had left the house with its large garden where he lived when I first met him, he had nowhere to put it. So he took it to where it would finally belong.

No one I know has been to his village, or even knows its name. I hope someone who was around when he died knew what he wanted, and made it happen. I hope too that they knew what kind of a send-off he would have wanted. Here again, we can only guess. That he was a Christian at birth – another of the stories about him – seems unlikely. I know for certain that at the sound of the muezzin he would close the shutters; and everything about him suggested this was not only for the sake of his eardrums.

There is so much we don’t know. And never will. For instance, where did the Palissy ware bowl and the many beautiful objects he sold or gave away come from? And what about the palatial house, with its garden full of antiquities, to which his little bookshop was an annexe? My guess is that it belonged to a wealthy foreigner: that Kemal was his manservant and became his heir.

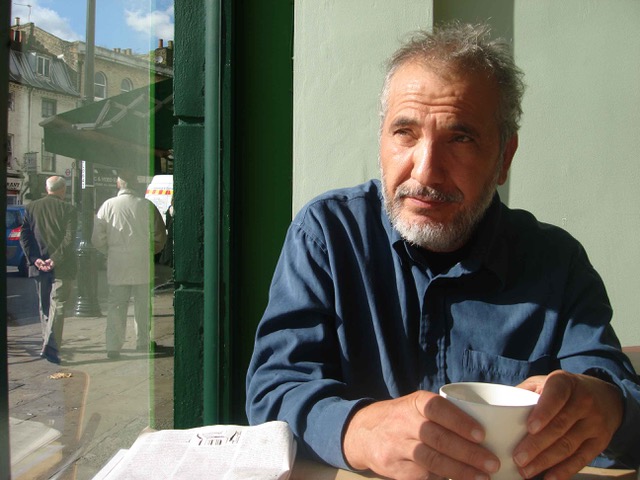

If we seem here to be in the realms of popular fiction, or even crime fiction, so be it. Kemal, in his beauty (‘a Neptune arising from the sea’, is how one of his highly educated lady friends describes him) is a story-book creation come to life. How appropriate for someone who so loved books.

What kind of books? had been my first anxious question when, months after exchanging addresses, and never having expected to hear from him again, I got a scribbled note asking me to buy books for him, and saying that a lorry driver, already on his way to England, would come and collect them.

And so began the four years of trawling the charity shops for any book that cost no more than two pounds, was in good condition, and I would want to read myself!

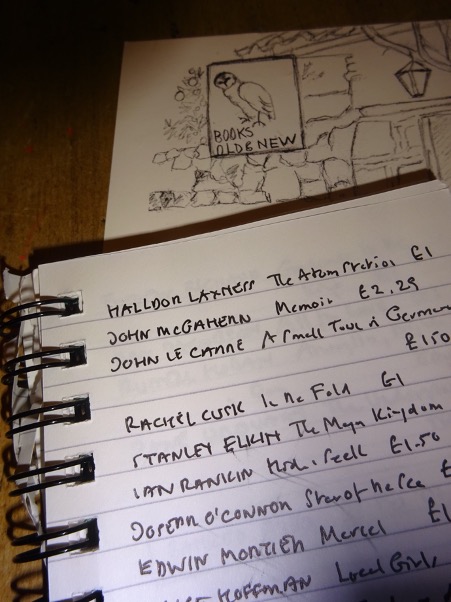

Here is a page from the notebook in which I entered each purchase:

Joan Didion Where I Was From £1

Reginald Hill Death’s Jest Book £1. 50

Andrea Ashworth Once In a House on Fire £1

Rachel Cusk Saving Agnes 70p

Ian Rankin The Falls £1

Proust Vol 4 Sodom and Gomorrah £1

Don Delillo Underworld £1

Graham Greene May We Borrow Your Husband 75p

I hadn’t read them all, and still haven’t. But each author or title whetted the appetite. In the case of Proust, my own appetite had, in truth, been satisfied long ago by the end of volume 3, but the title of volume 4 seemed likely to attract a browser’s attention.

Whether it did or not, I will never know. Nor will I know what has become of the stunning collection of antiquities, dragged out of skips, gathered from building sites – ‘the dustbins of history’ (here Kemal was quoting Trotsky) – and now displayed amid the tangle of shrubs and flowering trees in that garden, which I had glimpsed that morning when I first entered the shop.

That same morning, my husband was looking at antiquities too. But in the local museum. Antalya was not a destination, but a stop on the way from the classical glories of the western coast to Beyşehir, a small town in Anatolia, renowned for its ancient wooden mosque.

There were no museums In Beyşehir, which we were to reach a day or two later, but this was to be the most memorable of all our stops. A faded leaflet pinned to the board in the only hotel showed something that looked like a well and claimed it dated back to Hittite times.

Wishing Kemal was with us, for no one spoke a word of English, we still managed to find it: a water hole in a flat, empty landscape, with a trickle of water issuing from a pipe which – such is the power of suggestion – appeared numinous in the gathering dusk.

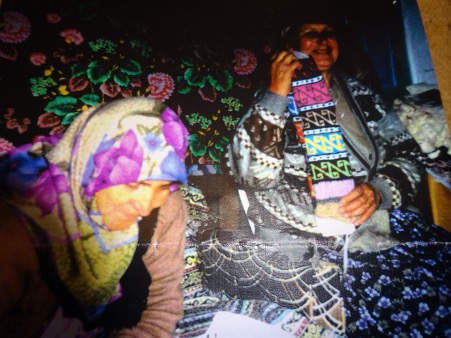

Who knows how long we would have stood there in wonderment, if we hadn’t been distracted by the sight of a small crowd of women, approaching slowly across the scrub. When close, they emptied sacks they were carrying onto the ground and there were mounds of knitwear – sweaters, hats, gloves, scarves, in all the colours of the rainbow – spread out for us to buy.

It is a regret to this day that I did not have the entrepreneurial skills to have magicked that beautiful handwork into some Knightsbridge boutique and given much needed custom to that remote community. But this short-lived dream, which had Kemal as the middleman, lasted no longer than any other day-dream, and second-hand paperbacks remained the cargo which an increasingly unreliable lorry driver carried from England to Turkey.

In the long exchange of e-mails, the lorry driver makes many appearances:

Hope lorry driver doesn’t forget the books this time everybody seems to get alsemeir . . .

He is still in Italy . . .

Am I right in thinking we can’t expect lorry driver during Ramadan?

And then, inevitably

I am terribly sorry, but lorry driver is kaput

My memory lets me down there. Did K find another driver bringing cargoes of lemons to London? I think he must have done, because my ‘sales ledger’ tells me another year passed before things finally came to a stop. By then, I was haunting the charity shops not just for Kemal but also for my grandson, Zachariah, to whom I sent a book every month for his first five years.

Now 12 years old, Z is lost to me (though not to books) in the baffling world of Manga, and the charity shops, thanks to Covid, have long been out of reach. Those halcyon days are over when ‘buying for Kemal’ was a part of life and R and I would scour the high streets of market towns for Heart Foundation shop signs, and the back of the car was always full of books.

But the memories linger and they are not only about books. There was the time when Kemal came and stayed with us: the only time, except for that encounter in the shop, that he and I were in the same place at the same time. It was during this visit we discovered what a wonderful and willing cook he was. He loved food, as he also loved flowers: he recognised almost every one that was growing in our garden, and had grown many of them in his.

Was it an illness of mind or body that made this man, with his lust for life and love of beauty, die as he did? Or was it the increasing ugliness of the world that made him want to leave it? Whatever it was, it is over now.

Wherever you are and however you got there, Kemal,

rest in peace.