In the habit of blogging, once a month, I am resurrecting the March post (which I took down almost as soon as it went up) with additional narrative to bring the story up to date, for it is now more pertinent than ever. The only significant change is that the number of GPs who have failed us has risen from seven to nine.

It was the 23rd of November, eight months to the day since the start of Lockdown. We were taking our regular early-morning walk in Regent’s Park in preparation for yet another housebound day ahead, when R’s legs gave way. Able to move but frighteningly unsteady, he made it back to the car and I drove us home. And thus began a living nightmare which we have only just survived intact.

No one could have prevented the onset of what we were eventually to learn is a well-known condition, but there were myriad opportunities for diagnosis, had we ever seen a doctor. As it was, during those interminable weeks (which stretched into months) when we initially had no idea what was happening, were then allowed to think it was Parkinson’s Disease, and at no point knew how best to handle it – we did not see a doctor once.

Parkinson’s came into it for this reason: R was, indeed, being treated for it, but it was at such an early stage that we had been told, convincingly, that death was likely to upstage it: one of the benefits of old age being that one may outwit the slower-paced killers.

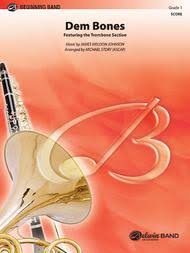

Looking back now that R has started to recover spontaneously, it is hard to believe there was a time I didn’t know that a sudden loss of mobility is almost certain to stem from the spine. The writer of Dem Bones, that spiritual inspired by the book of Ezekiel and set to music by James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) would have been less easily fooled than we were. Dem Bones, with its jaunty ‘. . . the knee bone’s connected to the thigh bone . . . ‘ says it all.

No, it was not Parkinson’s. It was something called Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, which I now know to be a narrowing of the space between the vertebrae, very common at our age and generally due to the dehydration of the discs and years of bad posture.

Why did no one think of this or of NPH (Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus) which also causes sufferers’ legs to suddenly give way? But, as NPH is often mistaken for Dementia, it was perhaps lucky no one did think of it, as R has always said he would rather anything than lose his mind. I, on the other hand, would rather prefer (as my multi-lingual Italian aunt would say) to be permanently befuddled than in constant discomfort. We were better off thinking he had galloping Parkinson’s than that he was losing his mental faculties.

As to why no one thought of it, the answer is simple. They never saw him. They were just voices on the phone. Not one of the seven doctors I spoke to had suggested – or, when asked, been willing to make – a home visit. It was not until a routine hospital appointment that, almost nine weeks after that fatal walk, R actually saw a doctor, and that doctor, seeing the way he walked, referred him straight on to the Department of Spinal Neurosurgery.

It is not surprising that the one medic who had seen R – a young male nurse who arrived to take a blood sample a few hours after my initial call to our GP practice – did not have the experience or training to recognise the symptoms. He came from an organisation (Rapid Response) whose dual function is to try and keep patients out of hospital (a laudable enterprise at all times, and the more so during a pandemic) and to lighten the GP’s burden by carrying out simple but essential procedures.

To lighten the GP’s burden . . . how my doctor uncle (one of five Estonian-born doctor siblings) would have welcomed that!

But how he would have scorned the idea of treating a patient without seeing him. And surely no one of my age can forget the tongue out, hands-on procedures which almost any visit to the doctor once entailed.

Of course, there is nothing like having grown up with a doctor in the family, and I was to acquire two more on my marriage.

But what one really wants, of course, is not a doctor uncle and a doctor father-in-law (both long since dead) but every Jewish mother’s dream, a doctor son.*

And what one wants from one’s GP, when things are serious, is his or her physical presence.

*The greatest comfort I had during those stressful weeks, from anyone in the medical profession, were unhurried phone calls from the newly qualified doctor son of a concerned friend, now working on the wards of a Scottish hospital.

To bring the story up to the present:

When, in early April, R suddenly developed new and terrifying symptoms, Dr 8 did not offer to visit, but he did arrange for someone to come ‘later in the week’ to take a blood sample. There was, I think, one more inconclusive phone call with a Dr 9 before, three days later, the ‘someone’ arrived. But we no longer needed him for we had a last reached a doctor – Dr 10 (acknowledged below) – who responded at once to my desperate after-hours-call and stayed with us until R, now barely alive, was rushed to hospital.

As I write this coda, on the sixth day of R’s return following nearly three weeks in hospital and the diagnosis of a new and unrelated condition, I want to record that although the GPs let us down, I can’t find the words to express appreciation for what the NHS has done and is doing for us.

We are being looked after at home – as we were in hospital – with a degree of diligence and loving care by absolutely everyone, from the most senior doctors to the cleaners (who never complained that I was in their way, even though I most surely was).

Back at home, with a constant and welcome stream of nurses, carers, occupational therapists, et al arriving at our door, only the GP practice (our ‘primary carer’) has yet to make contact. In contrast, the two organisations responsible for providing our seamless 24-hour ‘care package’, have provided me with weekday and weekend phone numbers, and a real person comes to the phone, at all times of the day and night.

Our GP practice asks for calls to the Duty Doctor – that is to say, calls about something that can’t wait for an appointment – to be made before 11.00 am (only on weekdays, of course).

When, in a time that now seems aeons ago, I banged saucepan lids for the NHS, I had not given a thought to how very much more than Covid the doctors, nurses and ancillary staff were dealing with every day and every night.

The ambulance men were the first in a long series of ancillary workers and hospital doctors who (along with Dr 10) have entirely restored my faith in the NHS.