Having learnt, by chance, that a book I remembered lending to Craig Brown some forty-odd years ago (when we were working on the The Dirty Bits) was now worth quite a bit of money, I dropped Craig a line c/o The Oldie. Though we had not met since, he answered by return and in friendly fashion, but where my signed copy of The Book of Grass is now, remains anyone’s guess . . .

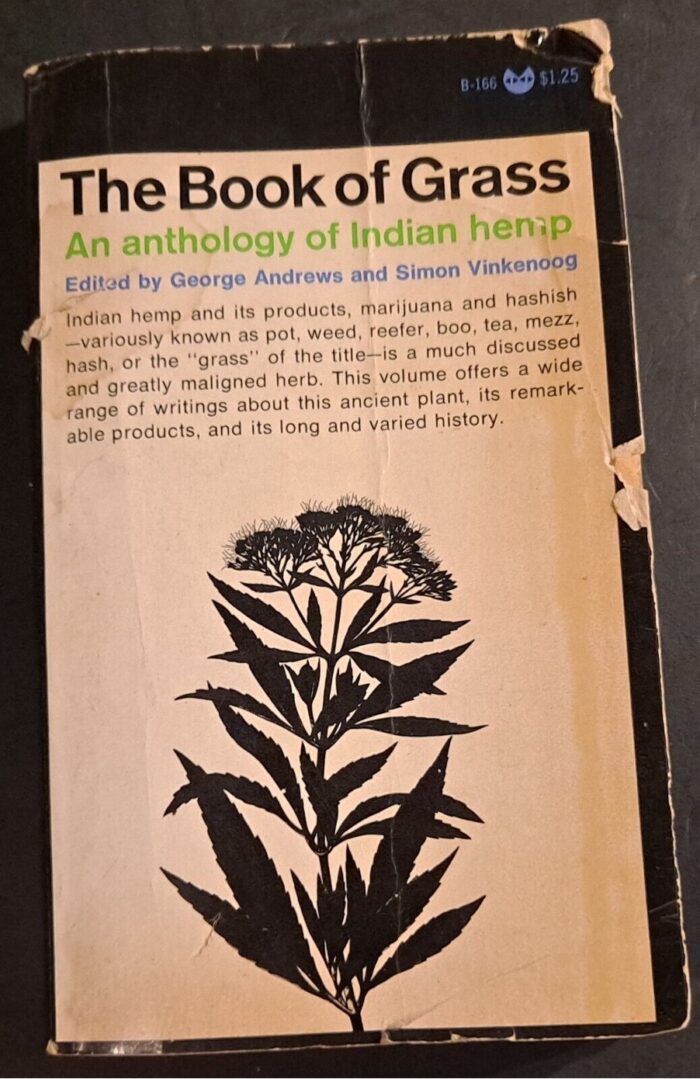

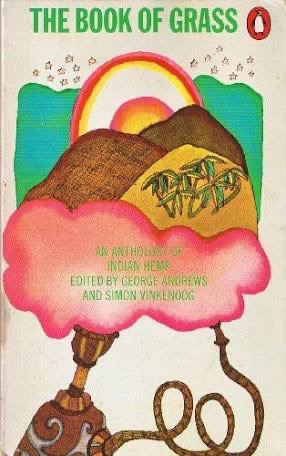

I had met George through M who I had got to know when she and her parrot were in the room next to mine at St Hilda’s in Oxford, where we were both reading English. As adventurous in life as she was intellectually (among her publications: Sixteen Takes on a Self-Invented Woman and The Hidden Library of Tanith Lee), she became a lifelong friend, and it was through her that I met many characters on the edge of polite society, two of whom, were to become my lodgers. One of these was George Andrews whose Book of Grass: an anthology of Indian Hemp has become a classic.

I was not interested in marijuana but had no objection to it – except as a substitute for the rent. When I told George I did need the two pounds but I didn’t need the weed, as smoking just made me choke, he came up with some hash brownies as a gift. But these had no more effect on me than the LSD I had experimented with a few years before.

In spite of my shortcomings as a smoker, our relationship remained friendly if remote. He would appear briefly in the kitchen to spoon out some brown rice (all I ever saw him eat) or greet me with a beatific ‘Hi man’ as he floated past on his way to or from his room.

It did not alter even after the visit of his wife – a spectre in flowing robes with glitter on her eyelids – of whose existence I had not previously known. She came, went and was never mentioned again.

Most of the time I was aware of his presence only through the smell of pot, of which the house reeked throughout his stay: a stay which came to an end when I could no longer put up with the tsunami of phone calls. George was, of course, dealing and my house had become his headquarters.

He moved on without rancour – I had probably lasted longer than most of his landladies – and, not long after, I received a letter from an address in Wales, inviting me to stay.

Some twenty years later my jazz musician son found it hard to believe that at one time he had hated the smell of pot. As for what became of George: when I last googled him, I saw he was back in the States and his interest now was in flying saucers.