Like a lot of comfortably secular Jews, I was jolted into a different kind of awareness of my Jewishness by the new wave of anti-semitism which began, of all places, in the Labour Party. Here, in the wake of a week spent remembering Auschwitz on the anniversary of its liberation and watching David Baddiel’s brilliant documentary on Holocaust Denial, is something I wrote in the early days of that new awareness. I apologise for the unusual and inordinate length of this post: it is in the nature of the subject.

I have to thank Jeremy Corbyn for giving me the answer to a question

that I have asked myself on and off for years:

do I feel more English or more Jewish?

And, more recently, since Estonia has come back into my life, perhaps

more Estonian than either . . .

I have just come back from the polling booth where I voted Green. The first time I have voted anything except

Labour.

So, what happened? Well, Jeremy Corbyn happened. Like so many people, I was thrilled when he appeared on the scene. I paid my £3 and re-joined the Labour Party and, though there were periods of concern, the Manifesto restored faith. Here was a vision of the future that I could believe in and wanted to help bring about. Even if it seemed pie in the sky to some, to me and many of my friends – almost all of whom would be left worse off financially from the changes he would bring about – it was worth aiming for.

The new Jeremy has found his voice and talks loud and clear to the jubilant crowds who stand ankle-deep in water to get a glimpse of him, so a friend who was at the Pateley Bridge rally tells me, and we all feel we may, at last, be on the path to victory, to a fairer society than the one in which we are so deeply mired.

So, what went wrong? To some, his

sober sidekick has always seemed a somewhat malign presence. But not to me. I was glad to have a softly-spoken suit

alongside the revolutionary front man.

And soon there was talk of dissension among the ranks. But this is not unusual in a political party

and is manifest among the Conservatives.

It was the trickle of anti-Jewish stories, at first among the rank and

file, but soon among more prominent members of the movement which caused real unease.

Soon, the trickle became a stream.

Why was there no serious attempt to do anything about it? There is, of course, no way of dealing with

the anonymous nutters who use Corbyn supporters’ websites to spout their poison. But what about the many known cases of party

officials with deeply unsavoury views?

And what about Corbyn himself? For a long time I have been arguing with friends who cannot forgive his having ‘shared a platform’ with Hamas and Hezbollah. What is wrong, after all, in talking with those with whom you disagree? But the lack of conviction in his handling of the shows of anti-Jewish feeling among his known followers, culminating in the business of the Tower Hamlets mural, has shaken me. Who wants a leader who has so little historical sense that he cannot recognise what is obvious to just about everyone – not only to Jews? And do I want a leader who talks off the top of his head? He later regrets that he ‘didn’t look more closely’ before he spoke.

None of this, nor the long list of his associations with declared

anti-Semites has made me think that Jeremy Corbyn is an anti-Semite. It

makes me think he is a fool, albeit a holy fool. And it makes it clearer than ever that he is

one of the thousands of English men and women who equate us, the English Jews,

with what is going on in Israel.

But why do so many people blame an entire country and, indeed, an entire

race, for its government? We don’t blame

all Americans for Trump, or all Burmese for the horrors occurring in their

country, or all Hungarians for having voted in a Fascist . . . And

what about us? Our deplorable government

should, by this logic, make pariahs of us all.

How grateful I am to the Greens who, when I found myself unable to vote

Labour, provided an alternative. And how

lucky to live in a borough that will never be anything but Labour, so my vote

is not going to dislodge the party I have supported in the past, and hope to be

able to support again in the future.

But how, as a profoundly secular Jew, can I explain this defection? I think the answer lies in the distant past,

on the day when I came down to prayers, in the Great Hall of the boarding

school at which I was a happy pupil, and being a few minutes early, looked at

the newspapers laid out on the chest under the over-hanging minstrels’

gallery. There, splashed across the front page of the Express was a picture of two broken-necked

bodies hanging from a makeshift gallows.

Two British soldiers murdered by the Irgun.

I knew then, and have known ever since, that I and the Cohen sisters and Elise Morris and Hilary Hockley, who made up the quota of Jewish pupils, were different, and however good we became at games, however many badges we had on our girl guide uniforms, however many films Mr Cohen [1] lent the school, we could never be quite like everyone else.

And so it has remained. I am English, yes, but I am also Jewish, and rational doesn’t come in to it. I can hold my fire, with ease, when an ignorant old man who I am helping to get re-housed, delivers a diatribe about the Jews – wherever did he hear of the Protocols of Zion? – on the doorstep. I can take it in my stride when one of my long-term employers (Jewish himself) makes me reject a remarkable offering (the story of a Guatemalan Jew) because ‘Jews don’t buy books’. I break off relations with a Death Row prisoner – a Biblical Zionist – when he insists that Hurricane Katrina was the God of Israel’s revenge for some recent incident on the West Bank.

It is easy to dismiss ignorance and stupidity, but not in the leader of

a political party.

And now a third element has entered the ring. Not just English and Jewish but also Estonian: not that Estonian Estonians would consider me Estonian and whenever I am asked where I come from, I always qualify my answer by adding that I’m Jewish. But my mother, being a direct descendant of the Nicolas Soldiers (those few Jews granted permission by Tsar Nicolas I to live outside the Pale of Settlement, also known as ‘Cantonists’), was as Estonian as a Jew can be – one of the four thousand who lived there before the war wiped most of them out.

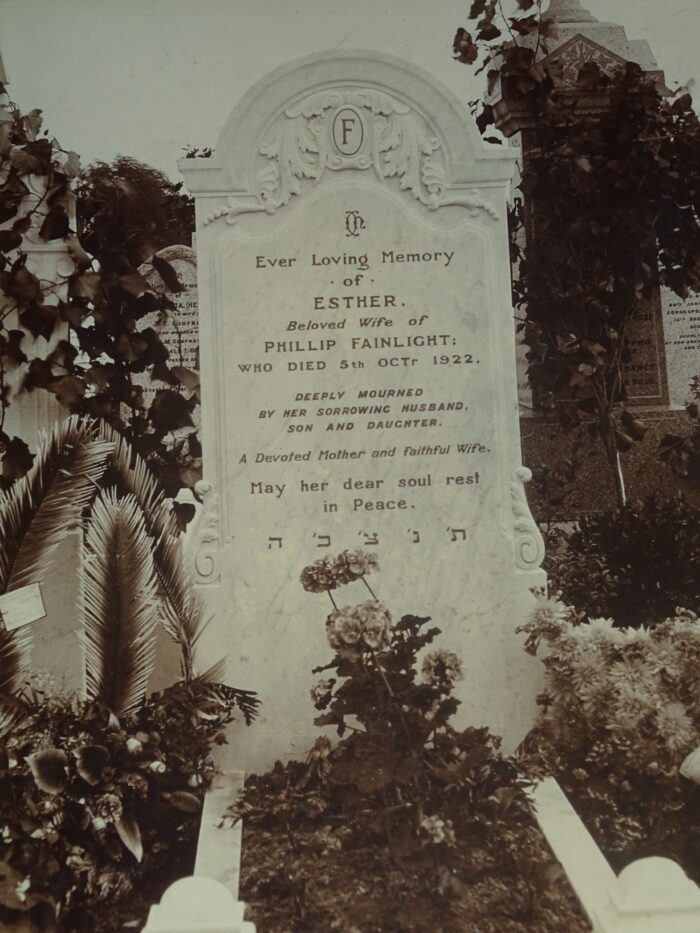

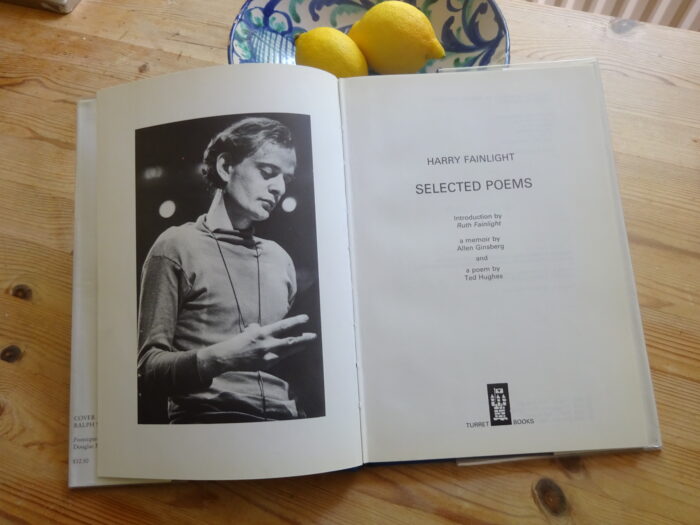

And not only my mother. My proudly English father was born just five years after his father arrived in London from Estonia, and one year after that same Mendl Grodzinski married Esther Hoff of Viljandi in the Stepney Green Synagogue, and became George Menell.

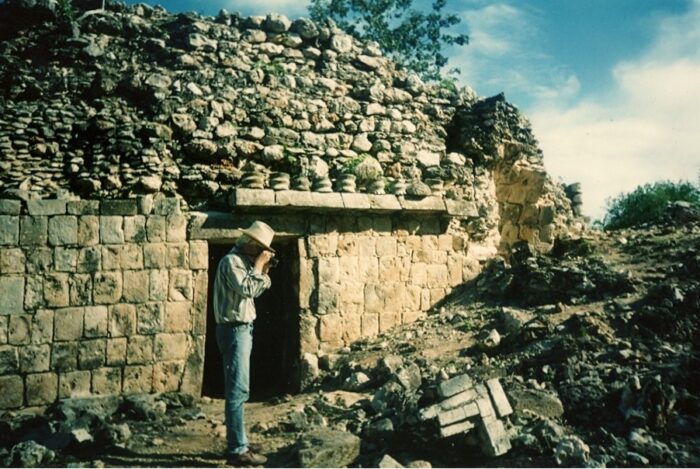

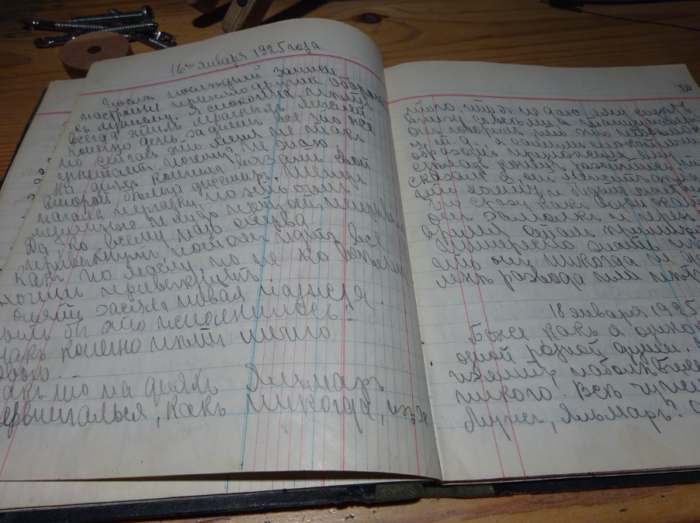

I owe knowledge of the date and place of my paternal grandparents’ marriage to a remarkable man – an Estonian-born Israeli who came across a memoir I had written while he was trawling the internet, thanks, no doubt, to its subtitle which includes an Estonian street name [2]. Unable to locate me, this tireless researcher whose working life had been spent as an employee of IBM, tracked me down through my son who, as a musician, has an internet presence; and I will never forget the day when I received an e-mail from New York, telling me that an Estonian called Mark Rybak had come across my book and was trying to find me, and ending, ‘Mother, your book has come home.’

And so it had. There is now a

copy in the Jewish Museum in Tallinn, a museum which didn’t exist when I was

last there, at the turn of the century, and unimaginable in the early ‘60s,

when my mother and I – on a quest to find my brother’s birth certificate –

arrived at the small, dilapidated house in which the rabbi lived and which now served

as the synagogue, though all the holy paraphernalia had been removed to the

Museum of Atheism.

We never found my brother’s birth certificate but I was reminded of our quest the other day when – from the National Archives to which Mark Rybak had directed me – I received a lengthy document headed METROPOLITAN POLICE SPECIAL BRANCH.

Was I going to find that my grandfather – the former Mendl Grodzinski, who always had barley sugars in his pockets to give his grandchildren and would share with them the sugar lumps through which he sucked his lemon tea – was a criminal?

Happily, not. This document

proved to be his naturalisation certificate and from it I learnt that, on the

contrary, he was a respected member of the community who had ‘by 1920 given up

his tailoring business’ and ‘with the knowledge of design which he had learned

in the tailoring trade commenced to design a retort . . . ’

This retort, as I was to learn from

Burning Stone: Estonia and the Menells,

posted by Mark on the Estonian Jewish Archive, was of vital importance in the

early days of the Estonian oil shale industry, an industry which, according to Wikipedia

‘is one of the most developed in the world’ and Estonia ‘the only country in

the world that uses oil shale as its primary energy source.’

So much for the Englishness of the English side of my family. Time now, to turn to my mother’s side.

The Gutkins – anyway, the male line, for my Gutkin grandmother was born in Lodz – were, as already mentioned, descended from the Nicolas Soldiers. Among them was Hirsch ben Jeddige Gutkin who would, I like to think, have looked something like the old men in those oil paintings we see in one of the most delightful sequences in ‘Menashe’, that Yiddish-language film which has given me an idea of what he must have sounded like.

And what Mendl Grodzinski would have sounded like too. For though, as I discovered only recently, he was born not in Estonia but in Belarus [3], Yiddish would have been the language spoken in both my grandfathers’ homes. And how familiar it sounds to me. Another of those visceral connections which swung my vote. Or perhaps it is just that German (spoken by cook and nanny) were as familiar to the four-year-old me as English, when we left Estonia to return to England at the outbreak of war.

It is to my cousin, Ephraim (Fima) Zaidelson, the one English speaker among all my Estonian relatives, that I owe what I know of my mother’s family and there is a wonderful irony that, at the moment that I break loose from the Labour Party, I am indebted to someone who remained far to the left of me for most of his life. Known as Comrade Zaidelson at the English public school where he was a pupil when war broke out, Fima’s loyalty to the Party never faltered until reality became too much even for him. Here he is, caught in a nutshell by a school friend [4], visiting Tallinn, in the 1980s:

. . . Poor Jefim. On the wrong side of the twentieth century at every turn: despised by the Nazis for being a Jew, by the Russians for being Estonian, by the Communists for being bourgeois, by the Estonian nationalists for having fought for the Red Army . . .

But not only did Fima survive the war [5] and the collapse of Communism, he lived on into his nineties alongside his wife, Lena, also a child of the bourgeoisie, and they both lived to see Gutkin’s, the department store and long-time family business, restored to its former glory, whilst their children and grandchildren will inherit the gothic pile [6] which had once been their family home.

The election is over. Labour failed to take Barnet and I have taken the long overdue step to have my parents’ headstone cleaned. The nice Irishman who has been caretaker of the Jewish Cemetery in Kilburn for years, will see to this for me. I wish he could also help me set up a headstone for my aunt – my mother’s sister – who lived in Trieste and left me the money to do so. The complexity of this task defeated me and the only comfort is remembering the beauty of the graveyard in which she lies: a tangle of greenery and worn, lopsided stones, so unlike the businesslike rows in Pound Lane.

Cemeteries, of all places, help you discover who you really are. Not English, in my case, or I could be buried in one of the many hundreds of country churchyards visited when my husband [7] was writing his guide to English parish churches. But though I have only been inside a synagogue once since my first marriage almost sixty years ago, any Jewish cemetery would accept what is left of me. And had I been left in Tallinn with my grandmother when war broke out, being English would not have saved my life.

So, however English I feel and sound, and though my chosen resting place

(as ashes, of course) is a very particular spot on the North Yorkshire moors,

there is no getting away from it: when

it comes to it, the answer has to be not English, not Estonian, but Jewish.

Dedicated to Mark Rybak born Tallinn 8.3.1945 died Tel Aviv 6.3.2018 and to my Brooklyn-born grandson, Zachariah Hawk, whose Jewish blood mingles with that of his Native American and African American forebears.

[1] Mr Cohen: Nat Cohen (1905-1988) summed up in Wikipedia as ‘the most powerful man in the film industry’

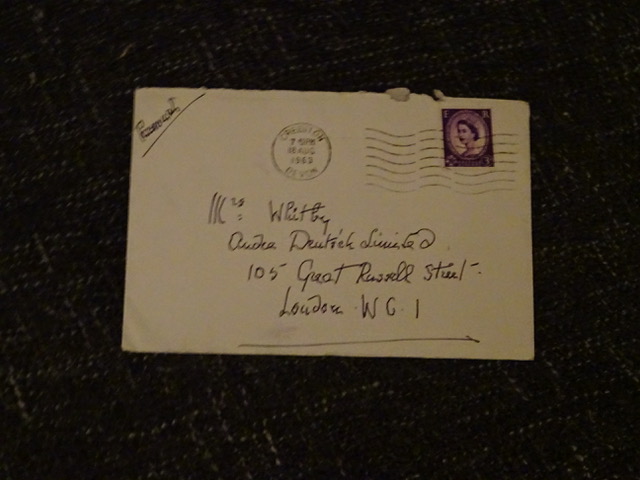

[2] Estonian street name: Loose Connections: from Narva Maantee to Great Russell Street, London, 2014.

[3] Belarus: in a town called Polotsk.

[4] a school friend: Frank Branston (1939-2009) an alumnus of Bedford Modern, newspaper proprietor and novelist.

[5] survive the war: The astounding story of his war in which – so emaciated that village women crossed themselves as he passed – he wandered from place to place determined to fight the hated enemy but so inept a soldier that he was finally put to use composing patriotic songs, is told in a letter he gave me which can be read – called Fima’s War – on the EJA website.

[6] Gothic pile: This mansion, built by Lena’s father as a family home, was requisitioned by the Soviets and became the Tallinn Conservatoire.

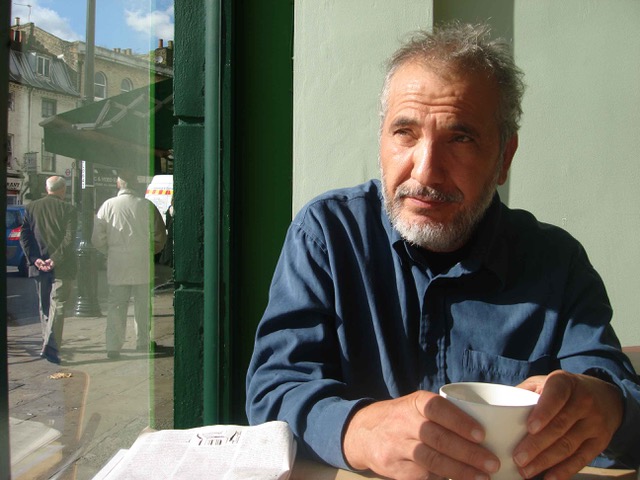

[7] my husband: Grandson of a Methodist minister, my American husband, Robert Harbison, wrote The Shell Guide to English Parish Churches, London, 1992.

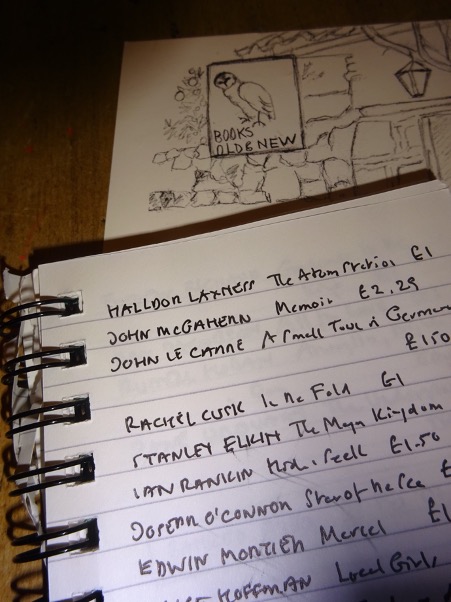

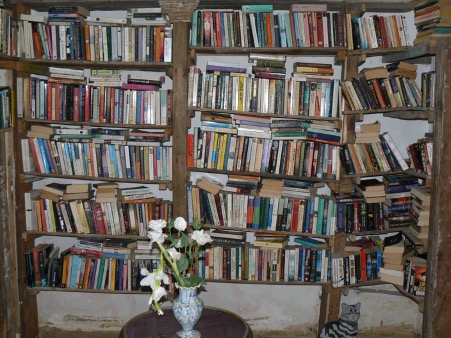

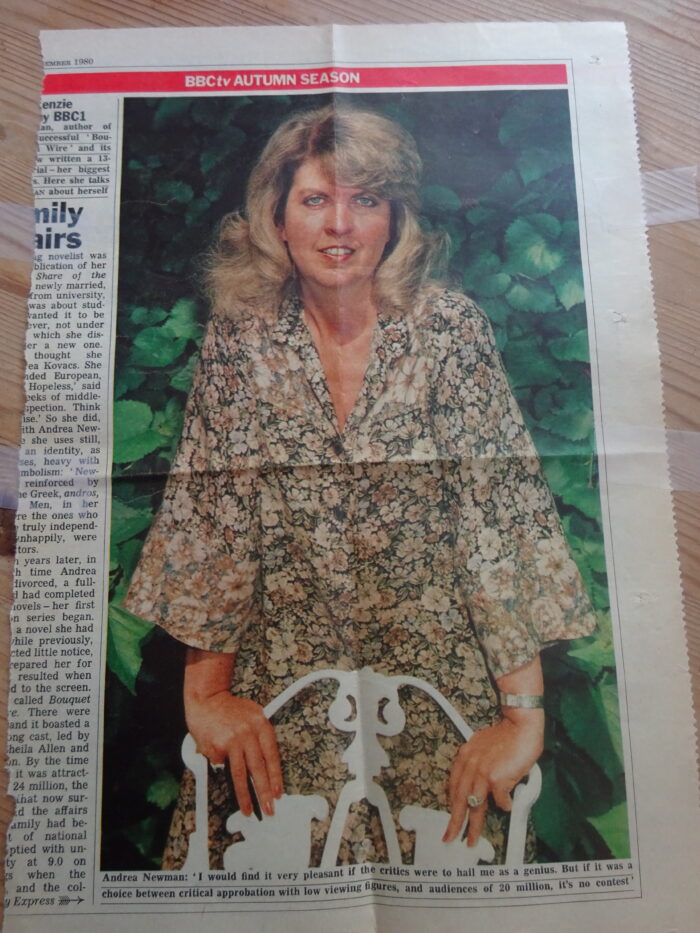

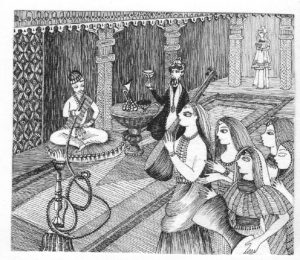

Hard as the initial step was – reminiscent of jumping into that cold Finnish lake, when honour-bound to join in a communal sauna – getting rid of photographs is quick work. Infinitely slower is all the other stuff and, as I battle my way through a lifetime’s accumulation, I wonder at the stamina of serial biographers. Of course, they are mostly trawling through papers which a professional archivist has already put into some kind of order. They are not going to find, as I have, the originals of illustrations for a children’s edition of The Arabian Nights interleaved with handwritten notes to my deaf father-in-law: ‘I never have oatmeal or orange juice or prunes for breakfast’, nor

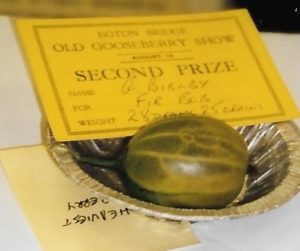

Hard as the initial step was – reminiscent of jumping into that cold Finnish lake, when honour-bound to join in a communal sauna – getting rid of photographs is quick work. Infinitely slower is all the other stuff and, as I battle my way through a lifetime’s accumulation, I wonder at the stamina of serial biographers. Of course, they are mostly trawling through papers which a professional archivist has already put into some kind of order. They are not going to find, as I have, the originals of illustrations for a children’s edition of The Arabian Nights interleaved with handwritten notes to my deaf father-in-law: ‘I never have oatmeal or orange juice or prunes for breakfast’, nor  the picture of a prize-winning gooseberry stuck to the cover of an ancient issue of Isis which has in it an article by John Gross who, in those days (February 1957) seemed to me like just another nice Jewish boy . . . .

the picture of a prize-winning gooseberry stuck to the cover of an ancient issue of Isis which has in it an article by John Gross who, in those days (February 1957) seemed to me like just another nice Jewish boy . . . .