The title of this post, written a day or two before the events in North Kensington, has become horribly topical, but this was the question put to me, on my doorstep, almost half a century ago, by a Camden official.

What do you mean? Where would I like to go . . ? He looked surprised that I didn’t know what he was talking about.

It took a few minutes to discover what had happened. And it took four years to fight off the Council.

It turned out the plan to re-develop the street I live in, where the ‘bijou workmen’s cottages’ (built in the late nineteenth century for railway workers) now change hands for over a million pounds, had been drawn up years before, but only passed for action at the tail-end of a meeting about CentrePoint, by which time no one was paying attention.

One of the proofs that they had not done their homework was the man with the clip-board’s surprise on hearing that I was not a council tenant, as almost everyone else was, but was buying the house (which then cost £4,500) with a Council mortgage.

And no, I did not want to move to Woolwich or Eltham or Thamesmead (nowadays it could be Gateshead or Birmingham).

But neither, to my shame, had I noticed that everyone from the other side of the street had already been decanted.

Somewhere, my husband has written of the learning curve that he experienced and delighted in after agreeing to give a course of lectures on the entire history of architecture. Every week he was tackling a new civilisation! Well, this was to be my learning curve, for there is no more sedentary and back-room job than being a book editor.

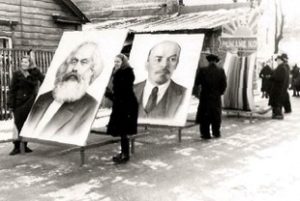

Along with my two neighbours, the only other owner-occupiers in the street, we formed a Residents Association of which the Chairman was my next-door neighbour John, electrician and Communist Party member*; the Treasurer was Bill the builder, a working-class Tory; the Secretary, me.

For the next four years, I became a mix of pamphleteer and social worker. I learnt as much about the inhabitants of this street and the weaknesses of local democracy as R was to learn about entire civilisations.

The arrogance with which people are treated! For once in my life I was glad of my middle-class accent; also of owning both a telephone and a typewriter. Not everyone had the first, and no one else had the second. In fact, in my survey of every household, I found one house had no electricity, and the old couple who lived there preferred it that way. Arguing their case (they were the age I am now) was one of my more unusual assignments.

Looking back, I feel lucky to have had the chance to do something worthwhile: my proudest achievement was arguing the Council into allowing their tenants to move into the empty houses across the street and then back again, after the re-hab which took the place of wholesale destruction.

I am not sure that my fifty-year old son has such warm feelings about this period when I was often absent at meetings and endlessly pounding the street, with him in tow, distributing roneoed information sheets.

Not that I don’t have one or two unsettling memories myself: at one door, I was greeted with a diatribe about the Jews. The old man didn’t realise he was talking to one and I didn’t tell him. And there was the young couple, one of the few tenants of a private landlord, who were embarrassingly grateful to me for getting them out of his grip, but were later to abscond with some association money . . . And then, to crown it all, by the time the long battle was over, our four local councillors had all left the area: one of them leaving behind him a house with an extra storey which still sticks out like a sore thumb, as no one since then has been granted planning permission for this most common of improvements.

You can’t win them all. And how things have changed! If the street were threatened now there would be a galaxy of lawyers, architects, journalists ready to spring to its defence. Meantime, the only topics that can be relied on to produce a torrent of e-mails are Litter, Parking, Noise and BINS!

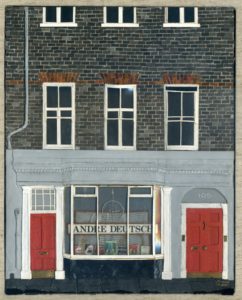

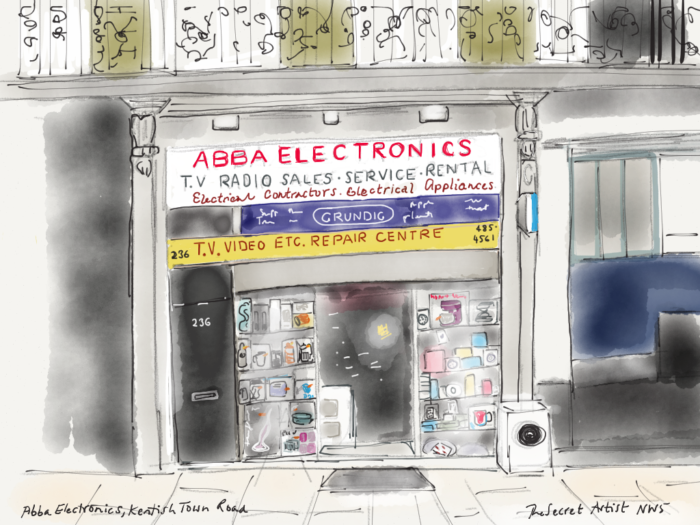

Which is why I preferred the way it used to be, and fear for the tenants who are going to be decanted from their homes to make way for the development of our local Morrisons site (see artist’s visual below).

They will be told they can return. But no one returned to the other side of our street.

* When he retired, John moved out of London and sold his house to Tessa Jowell. But that is another story.

I never got back to Eliot and his unfortunate wife* but, with the kettle on for my hot-water bottle and the Evening Pill Box – lovingly curated by my absent husband – at the ready, I did manage to tap out a testimonial for one of my long-ago authors** who, at seventy, is starting a new career as a hired-hand memoirist, to support her true calling as a brilliant but neglected writer of popular fiction.

I never got back to Eliot and his unfortunate wife* but, with the kettle on for my hot-water bottle and the Evening Pill Box – lovingly curated by my absent husband – at the ready, I did manage to tap out a testimonial for one of my long-ago authors** who, at seventy, is starting a new career as a hired-hand memoirist, to support her true calling as a brilliant but neglected writer of popular fiction.

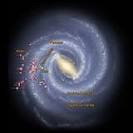

The discovery that dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars is just one of the many wonderful scraps of news I have picked up from turning on the BBC World Service when I come down to the kitchen in the middle of the night, to take some valerian drops or make a cup of cocoa. Another is that there is a language in northern India which has no name. Its 400 speakers just call it Our Language . . .

The discovery that dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars is just one of the many wonderful scraps of news I have picked up from turning on the BBC World Service when I come down to the kitchen in the middle of the night, to take some valerian drops or make a cup of cocoa. Another is that there is a language in northern India which has no name. Its 400 speakers just call it Our Language . . .

As Jilly Cooper said the other day, in a lovely piece about what it is like to be eighty, being up in the small hours comes with the territory; but these broken nights have, thanks to the World Service – truly a service – opened up not only new terrestrial worlds but also the firmament itself: how else would I have known when looking at the Milky Way that every dung beetle in our garden was looking at it too?

As Jilly Cooper said the other day, in a lovely piece about what it is like to be eighty, being up in the small hours comes with the territory; but these broken nights have, thanks to the World Service – truly a service – opened up not only new terrestrial worlds but also the firmament itself: how else would I have known when looking at the Milky Way that every dung beetle in our garden was looking at it too?