The other day, I heard or half-heard (Radio 4 stays on constantly in the kitchen) that ‘the Social Contract’ has been – or, perhaps, is about to be – broken, and with what dire consequences . . . And what appeared to be meant by the Social Contract was the contract between generations for children always to do better, to have a better life than their parents.

But what kind of sense does this make, unless one is talking about countries a lot poorer than our own? How could each generation do better than the one before: a snakes and ladders concept which would soon go right off the edge of the board.

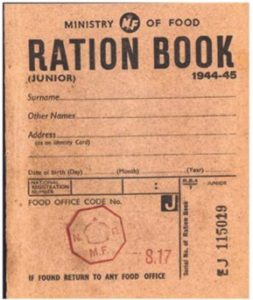

It is true, as my then teenage son pointed out long ago, that we – meaning me and his various parents – hit a good moment. When I think about it, not only were we able to get onto the housing ladder (not that we then thought of it like that), but we were too young to be unduly bothered by the war. I still have my shrapnel collection somewhere and have been left with a life-long appreciation of oranges and bananas, so plentiful now, but known only from picture books then. We were, moreover, protected from childhood obesity (another of today’s hot topics) by those buff-coloured ration books which, incidentally, also guaranteed equal shares for all.

But is that really what the Social Contract was about?

I had a dim memory of coming across the term in history lessons and googled it. And the answer, of course, was that the Social Contract went way beyond the disparity of incomes between generations. What concerned these great moral philosophers was an idea of something like universal sacrifice for the greater good and, particularly, the responsibility of government towards its citizens. Perhaps, too, citizens’ obligations to each other.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Certainly all these are increasingly rare. Everyone, it seems, is out for himself, like the Carillion bosses, so vividly described recently as ‘too busy stuffing their mouths with gold . . . ‘

Thomas Hobbes

And yet, and yet . . . the other day, also in the kitchen on Radio 4, I heard one story after another of people who had given up safe and well-paid jobs, to do something socially useful: bankers becoming teachers, accountants becoming social workers.

It seems that the precept of the Social Contract comes naturally to a lot of people, but not to those with the power to make life better for everyone, not just for themselves.