No. I am not going to pass. I am going to die. How can people be frightened of words? And, no, I do not want to be called by my Christian name by people I don’t know who don’t know me.

But at least we don’t have to deal with the confounded tu-ing and vous-ing that they do across the channel.

As a child one is naturally direct. Obfuscation, irony and all the twists and turns of language are still to come.

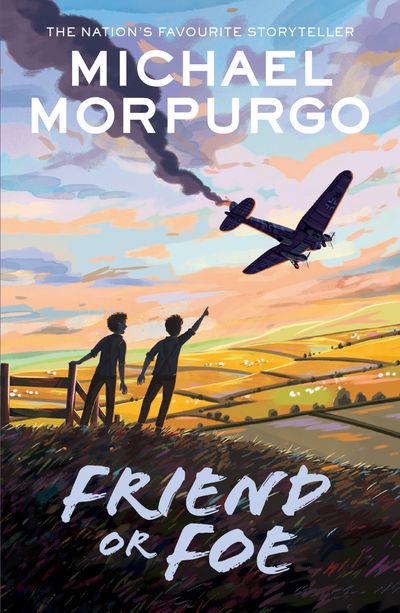

I will always treasure my eight-year-old son’s description of his much-loved tortoise which did nothing all day except shuffle about, bump into the wall and topple over, as ‘small, quiet and brave’; or the memory of myself, as a five-year-old, shouting FRIEND OR FOE? each time there was a knock at the front door. I was giving a very clear (if inappropriate) command, though it was not long before, to the delight of me and my friends, two German airmen, whose plane had crashed on the moors just beyond our house, did have to be rescued and were escorted away by the village policeman.

Such excitement was rare in that peaceful spot: excitement is far from rare as, spellbound, I watch an old BBC dramatization of Little Dorritt. Not unlike a child, Dickens saw things in black and white. He did not fudge experience by using euphemisms. His characters are, with a few exceptions, very good or very bad and death is death.

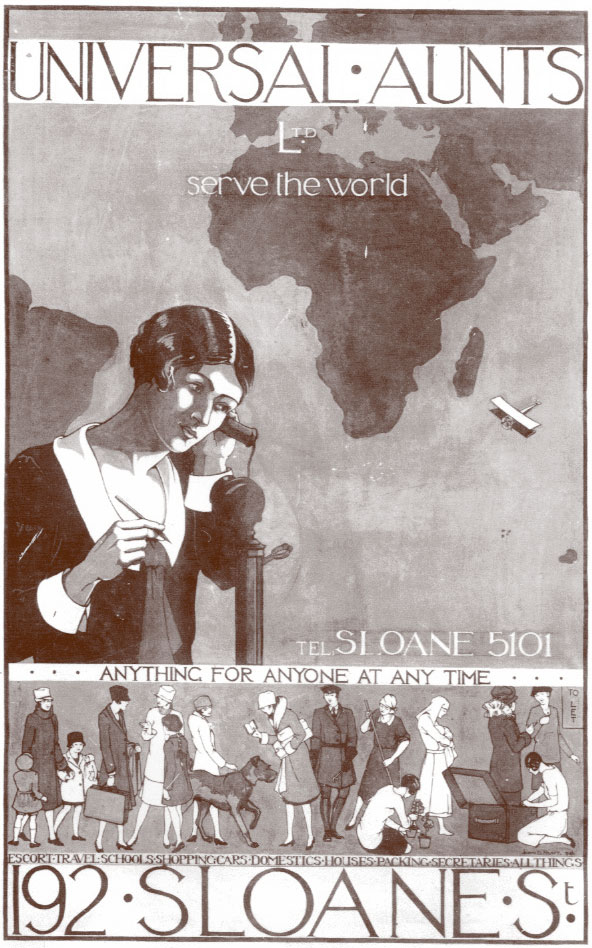

Things can go too far, of course, and blunt language is not always appropriate, but false intimacy is not the answer. One organisation which steers well clear of this is Universal Aunts. Every caller – and a person, not a machine, answers the phone – is addressed by their surname until a relationship has been established. Founded in 1921 by an unmarried lady at a loss for occupation when she was no longer needed to supervise the return from the colonies of all her nephews and nieces, it offered, and still offers today, to ‘do anything for anyone at any time’. A happy reminder of how things used to be.