As a stepping stone back to the present from the distant past, a memory from not quite so long ago . . .

It was my good luck that, in the early sixties, when I came to work in the editorial department at André Deutsch alongside Diana Athill, Jean wasn’t famous. Bequeathed to Diana by that remarkable truffle-hound Frances Wyndham who had in truth rediscovered her, she was no more than a name on the list of five ‘outstanding options’ which I inherited from my predecessor and which became the bane of my life.

With Frances Wyndham now long gone, the name Jean Rhys sparked no interest in anyone in the office except André, who raised it and those of the other malingerers at the editorial meeting every single week. He had paid her £50 and if that meant sending someone down to Devon to get the long-overdue novel out of her, so be it. And the person who went, as no one else offered to go, was me.

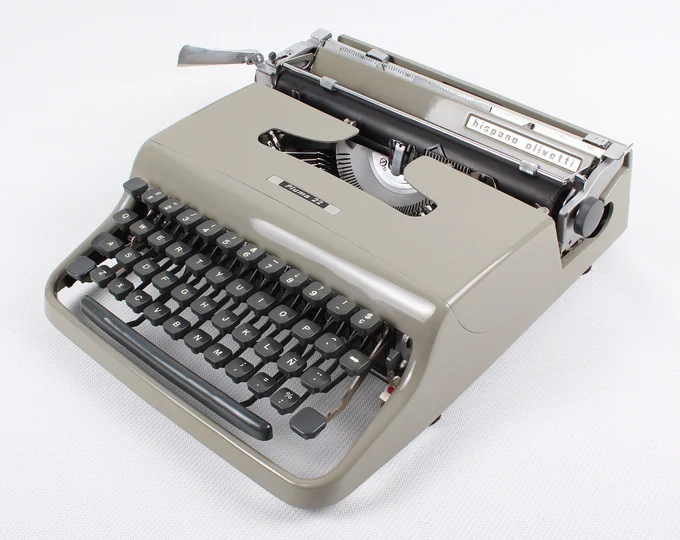

Briefed by Diana, who told me nothing about Jean except that she was old, in a muddle, drank too much and couldn’t type, I was happy to take a couple of days off from my own shaky marriage, packed my little Olivetti typewriter and took the train down to Cheriton Fitzpaine, where Diana had arranged for me to stay at the vicarage.

At the time the Reverend Woodward, a kind and scholarly man – one could imagine him playing cricket in his youth – was not yet a part of literary history as he and Mr Greenslade, the taxi driver, were to become in the excitement that followed Jean’s re-discovery: the initial boom now a cult, but still producing occasional works of real scholarship.

Be that as it may, I had a warm welcome at the vicarage and before long the Reverend Woodward – the one person in that benighted villages (as it seemed to Jean) who could understand her – was walking me down to the wretched little bungalow where she lived.

I will never forget the first sight of her as she opened the front door: small, fragile, quavery, her huge eyes downcast. She did not look long for this world.

In fact, she was to live for another ten years, but those days as her amanuensis (which I have described elsewhere) were to be the entirety of my role in her life. This was lucky for both of us: she needed someone more like herself, not someone with no taste for alcohol and no interest in pretty clothes, I would have been entirely out of place in the world she was about to enter.

But I feel lucky to have met her and to have had the privilege of typing out, at her dictation, several handwritten pages of Wide Sargasso Sea.